Book review: This novel teaches us how to live with nature with an evolved sense of environmental awareness

Anuradha Sarma Pujari’s novel Iyat Ekhon Aranya Aasil, which won the Sahitya Akademi award in Assamese literature in 2021, can be seen also as a pioneering work in ecocriticism in Assam. Based on the contentious issue of encroachment in the hills around Guwahati, the novel doesn’t take an aggressive stand. Instead, it seeks a humane solution, which can help mankind and nature co-exist. Such co-existence existed in the past, only humans have forgotten, fuelled by the greed of some and existential need of many.

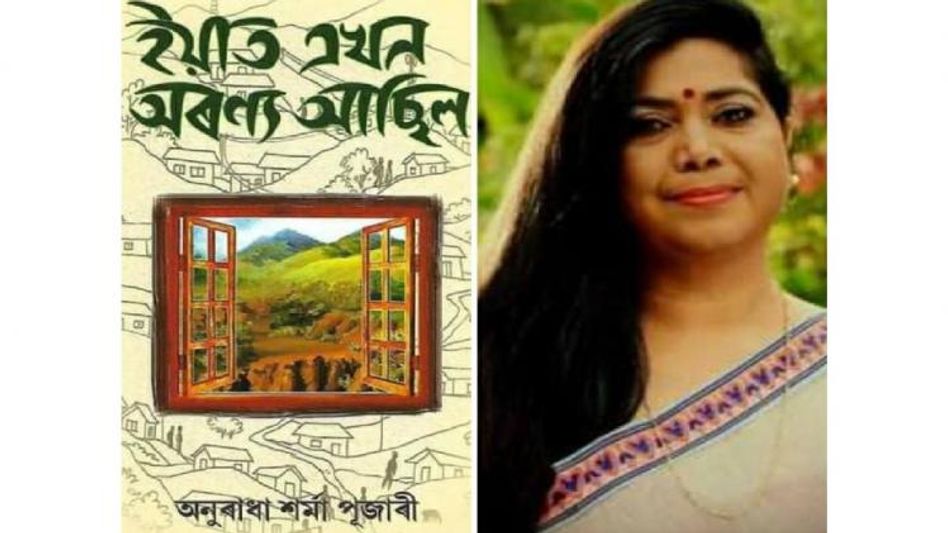

Photo credit: Cover of the novel Iyat Ekhon Aranya Aasil

Photo credit: Cover of the novel Iyat Ekhon Aranya AasilWhen environment changes and faces a crisis, there is a need to understand nature from a different and evolved perspective. Humans have to establish the relationship with nature anew. Lawrence Buell’s The Environmental Imagination is an important book on this subject. Buell, a pioneer in ecocriticism, has investigated the environmental awareness reflected in a text. One important thing he has pointed out is that human history is intertwined with natural history. It is unsafe to consider human interest to be the only legitimate interest in an environment. A text should make human accountability to the environment a point. Environment should be treated not as a constant but as a process. Such awareness might be a guide to anthropocentrism, which considers human beings as the reason for the existence of the world.

Ecocriticism is a new subject in Assamese literature. However, it brightens our hope to see that many young Assamese writers are aware of the environmental concerns. From this point of view, Anuradha Sarma Pujari's Iyat Ekhon Aranya Aasil (There was a Forest Here) has invited the attention of the readers. The central theme of the novel is encroachment in the hills around Guwahati. The novelist has not sided with the animals and the forest while keeping the interest of human beings aside. Her notion of nature includes the existence of humans, but she does not want the activities of mankind to threaten the ecological balance. She notices that the hills are full of human habitation and some families have been living there for more than half a century. Those people did not destroy the forest in the past.

In the context of men living in harmony with nature, we may remember what nature writer Richard Kerridge, who teaches literature in Bath Spa University, says about environmentalism and ecocriticism. He says that ecocritics responsive to environmental justice are not exclusively concerned with preservation of wild nature at the cost of the interest of the poor people. In her novel, Sarma Pujari has pointed out: “The people living with nature and people trading with nature are two different classes.” A forest worker tells the narrator, who is a journalist probing the issues of encroachment and eviction, that there are dealers of drugs and illicit liquor among those who have encroached the hills. The police are aware of such activities. The novelist is sympathetic to the poor people who are living in harmony with the environment.

At times, the narrator wonders whom she has supported. When wild animals come out to crowded places, forced by the destruction of their habitation, she feels pity for those unsheltered animals. But she cannot stand unmoved as a spectator when homeless poor people are evicted from their forest dwellings. There is an honest forest worker Ranjan, who is also moved like the narrator by the plight of the poor people. Another forest worker observes that the forest has been destroyed by a class of middle men brokers with the help of some dishonest persons in the administration and some elected representatives of the people.

Anthropocentrism keeps humans at the centre of the world and ecocentrism is at the opposite pole. Ecocentrism places the environment at the centre. The narrator in the novel is fully aware of it and the narrative develops with this awareness. The forest worker Rajbongshi raises a question: “Which government permitted the people to establish schools, temples, churches and mosques in Amchang sanctuary?” Men have killed birds and animals, poisoned fishes and they need everything. In this indiscriminate destruction, they might end up by destroying the environment they need for their own survival.

The ecosystem means some local conditions supporting life. In a certain environment, some plants and lives naturally survive. But forces from outside can change it. New species from outside can destroy it. Such an awareness is expressed by the narrative of the novel. The activities of men have destroyed the ecological balance. Rajbongshi reflects upon the environmental awareness in our culture and heritage. He finds that Hinduism has taught us to worship trees. Different gods and goddesses ride on animals and birds such as lion, tiger, elephant, bull, goose, and peacock. He concludes that some sages and philosophers in the past included those birds and animals as means of transport at the interest of preservation. The novel discusses encroachment and eviction from different perspectives.

An ecofeminist approach to the novel is also perhaps possible. American anthropologist Sherry B. Ortner has pointed out in an essay that in various cultures the idea that women were subordinate to men once prevailed. The underlying idea, according to Ortner, was that woman is closer to nature. They accept their own subordination and the logic of human domination of nature. This awareness can also be read into the narrative. Most of the husbands living in the hills get drunk in the evenings and beat their wives. Some husbands beat up their wives to take away their little savings to consume liquor. These oppressors are the people who destroy forest resources.

Ecocriticism and environmental awareness have been expressed in the novel in different terms. The narrator, as a journalist, collects facts about encroachment and destruction and identifies the destroyers. She is also an author and examines the life and struggles of the poor forest dwellers from close quarters. She shares the anxieties of possible eviction in the hill through Madhuri, who has been working in the narrator’s house.

In her fictional construction, the novelist has added another dimension to encroachment and eviction. It has been extended to a husband-wife relationship. The journalist’s friend Juti suspects her husband of having extra-marital relationships and is afraid that she might be evicted from her legitimate place. The intensity of her worries and anxieties is no less than Madhuri’s fear of a possible eviction. The ending of the novel is optimistic and sanguine. Chanda and her friend Raghu have come forward to save the ecological balance and environment. An interesting character in the novel is Monbor Doley, who is a mahout and can understand the language of the animals, and this is something important. The change in the awareness of the young generation in the novel brightens our hope. This optimism in the novel is conveyed through the image of Madhuri’s granddaughter, who keeps smiling all the time. Onlookers, who have forgotten to smile, also join the baby in spreading the happiness and hope.

Ananda Bormudoi, a former professor of English Literature at Dibrugarh University, is an eminent writer and literary critic from Assam.

Copyright©2025 Living Media India Limited. For reprint rights: Syndications Today