‘Colour My Grave Purple’ traces Assam beyond insurgency and myth

‘Colour My Grave Purple’ reveals Assam’s culture beyond conflict. It highlights the state’s people and everyday life with a fresh, balanced view

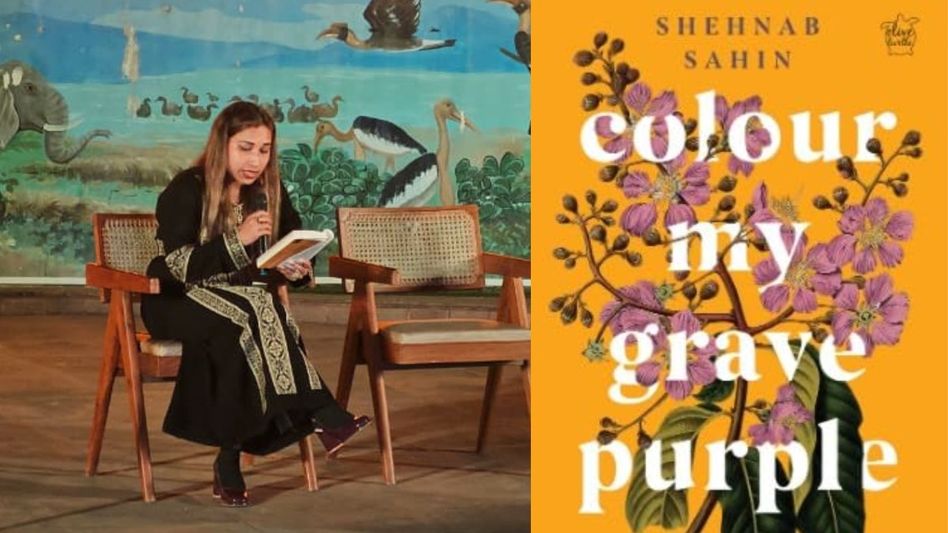

A new short story collection by Shehnab Sahin places Assam firmly at the heart of Indian historical fiction, shifting attention away from familiar tropes of insurgency and spectacle to everyday lives shaped by colonialism, conflict and change.

Colour My Grave Purple, published by Niyogi Books, brings together 10 stories set between 1855 and 2019. Rather than tracing a linear narrative of progress, the book focuses on what is often missing from mainstream histories: local voices, intimate struggles and the quieter consequences of power.

Sahin, a former civil services officer who now works in the international humanitarian sector with people displaced by war and conflict, is explicit about her intent. In the author’s note, she rejects the tendency to frame the Northeast as a problem region and calls for a wider representation of the Assamese experience. The collection responds directly to that aim, treating the region not as an abstraction but as a lived, complex space.

The opening story, Two Leaves and a Bud (1855), revisits the early years of Assam’s tea plantations through a British manager whose confidence in imperial order begins to unravel. The story foregrounds land appropriation and labour exploitation, using unease and the supernatural to expose the violence underlying colonial control. It sets a clear direction for the book: history is examined from the margins rather than the centre.

That approach continues in Bellows of a Wilted Poppy (1860), which explores the clash between indigenous healing practices and colonial medicine. Through the character of Rebo, a traditional healer experimenting with opium, the story highlights how systems of knowledge were reshaped—and erased—under imperial rule. Sahin’s deliberate use of untranslated Assamese underlines the limits of colonial language and authority.

Several stories rework historical figures and moments to question who gets to speak and who is remembered. Ursula (1943) imagines anthropologist Ursula Graham Bower from the perspective of the Naga communities she studied, turning the focus onto the ethics of observation and representation. Freedom in My Blood (1920) places a young woman within the nationalist movement, exposing how political awakening did not necessarily translate into personal freedom for women.

Later stories move into the post-Independence decades, including Devotional Defiance, which traces a young man’s queer self-realisation in the 1970s. Across periods, Sahin’s characters—tea workers, soldiers, missionaries, lovers and administrators—are written with attention to social context rather than symbolism, allowing personal choices to reveal larger structures.

The title story, Colour My Grave Purple, closes the collection by linking private grief with historical inheritance. Centred on the death of a father, it frames mourning as an act of memory and resistance, insisting on the right to name, remember and claim the dead in a landscape shaped by loss.

Taken together, the collection makes a clear intervention. By foregrounding Assamese lives across more than a century and a half, Sahin challenges narrow narratives of the Northeast and argues, quietly but firmly, for a more expansive literary map of India.

Copyright©2026 Living Media India Limited. For reprint rights: Syndications Today