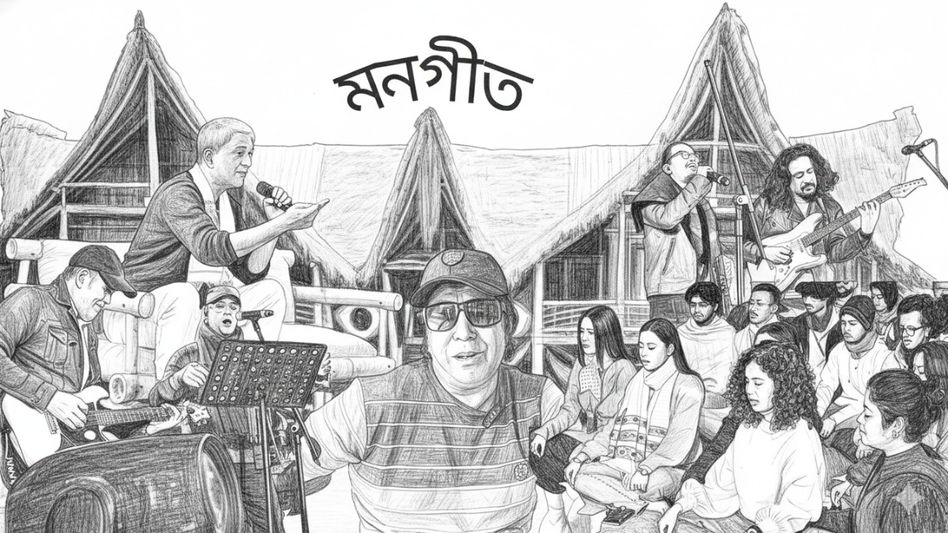

Why Assam’s music residency 'Mongeet' matters in a world that measures art by numbers

This is not a talent hunt, a retreat, or a feel-good art camp. Mongeet is a test of whether young artists can survive without validation—and still choose to create.

- Mongeet residency fosters originality with strict rules against covers.

- Kaushik Nath founded the residency in memory of his son Raul.

- Participants learn to trust instincts over technique in their art.

The first thing you notice at Mongeet isn't the music. It's the silence between the notes—when a young singer stops mid-phrase, looks up at a mentor, and asks: "But how do I make it sound like me?"

That question is why this place exists.

The journey from Guwahati began at half past seven on a January morning, the highway stretching through Tezpur and Kaziranga, past Jorhat's endless tea gardens. By afternoon, the road reached Nimatighat where the Brahmaputra churned blue and massive below the ferry. Forty-five minutes of water and sky. Then the real test: forty minutes bouncing through dust and ruts that barely qualified as road, past Mishing villages where bamboo houses stood exactly as they had for generations, until finally Dekasang appeared like a promise kept.

Kaushik Nath built the resort entirely from bamboo. "Poor man's building material," he calls it, though what rises from the earth looks like something between architecture and sculpture—two horns defiant and beautiful. The floors are cow dung mixed with mud. Your feet connect to the ground in a way hotel marble never allows. The river runs just beyond, close enough to hear.

"You know that Beatles song?" Kaushik asked one evening. "About the nowhere man making nowhere plans for nobody? That song lived in my heart for years. I never planned any of this."

But here is what grief does: it clarifies. In 2018, his son Raul drowned at twenty-three, saving friends who could not swim. Raul was studying filmmaking in Mumbai, played drums, described himself as "artist, musician, and dreamer." Most fathers would have built a memorial. Kaushik built a residency where young artists could become what Raul never got to be.

"What he wanted to know, what he aspired to—I turned that into something for the young people from our state."

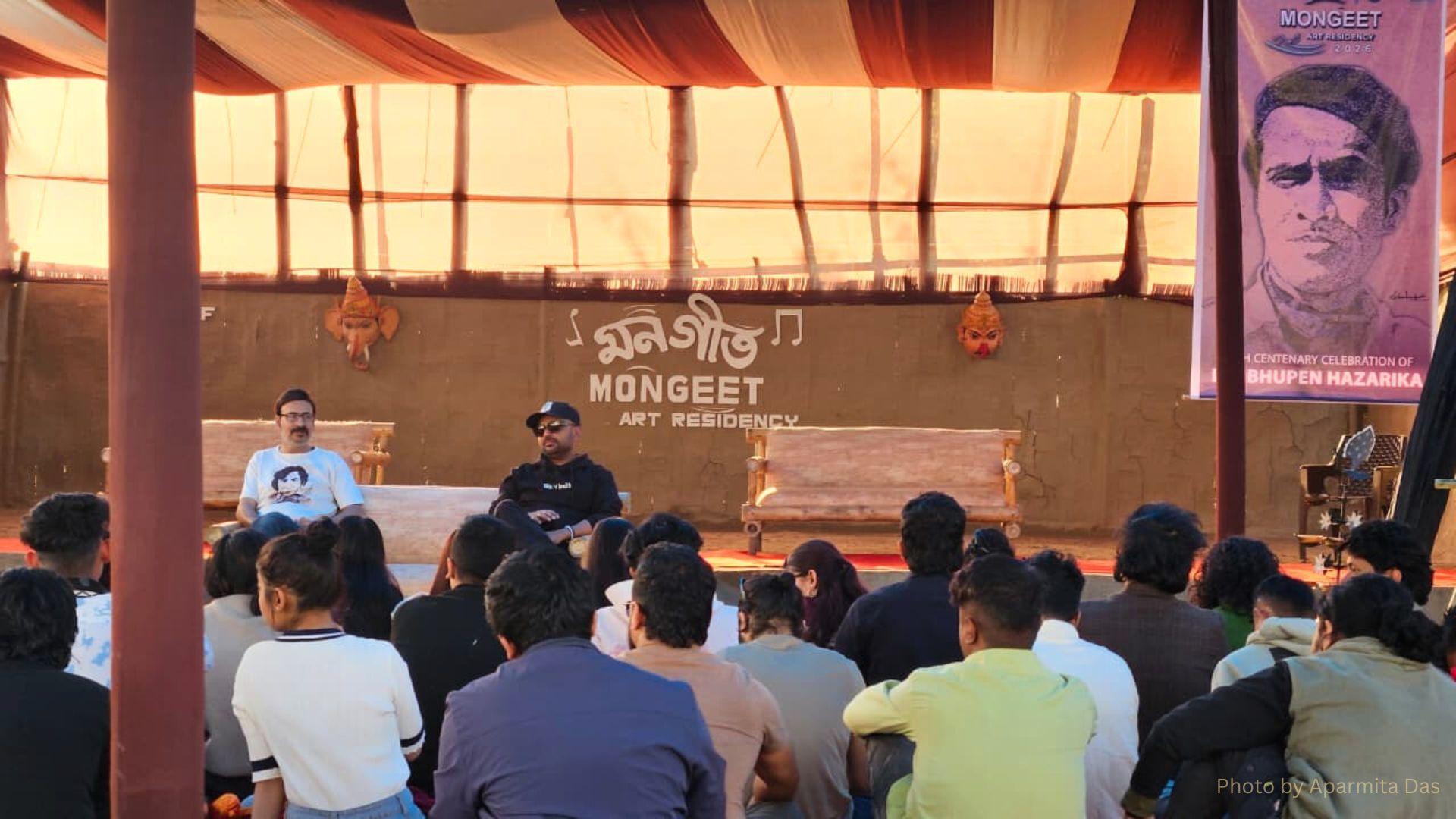

The Raul Kaushik Nath Foundation started in 2020. When Adil Hussain visited Dekasang in late 2018, the vision snapped into focus. Adil—an actor who has spent decades mastering the craft of performance across multiple languages and cinematic traditions, who approaches each role as a student approaches a teacher—understood immediately what Kaushik was trying to build.

He sat with Kaushik and Utpal Borpujari, a documentary filmmaker and twice National Film Award winner, and said something simple: "We've taken a lot from society. Now it's our turn to give back."

Every January since, Adil travels from Delhi at his own expense. No fee. No handlers. Just a National School of Drama graduate who once spent two and a half years on a Karnataka river island studying acting, now returning to another river island to teach what he knows.

"It's mainly for ourselves, because it feels good. Kaushik does all the work. I just come here like a guest, give some lectures, and take credit because I'm in movies," he said during a conversation. "That's the thing about cinema that bothers me most. Actors get all the credit when everyone else works just as hard."

Why Majuli specifically?

"This is the seat of Assameseness. Srimanta Sankardev is a saint who used nine or ten art forms to spread Vaishnavism. And what is Vaishnavism? Love without conditions. No hatred. Work without expecting rewards. Complete respect for every living being," Adil explained.

The satras—those Vaishnavite monasteries scattered across Majuli—have practised Sankardev's teachings without interruption for five hundred years. From sunrise to sunset, they sing Borgeet, they dance, they preserve what most of the world has forgotten. Beginning Mongeet by grounding participants in these ancient practices before teaching anything contemporary sends a clear message: you need to know where you came from before you can know where you are going.

This matters more now than ever. Young artists today grow up inside algorithms. Social media metrics tell them what they are worth. Music producers check follower counts before checking talent. Everyone sounds like someone more famous because originality feels dangerous, unprofitable, foolish.

Mongeet runs for ten days each January, this year from the 10th through the 20th. About thirty-five to forty participants arrive after a jury reviews over a hundred submissions and selects only original work. The rule is absolute: no covers, no borrowed melodies, no riding someone else's wave. You defend what you created or you do not come.

The days follow different rhythms depending on when you arrive. The first stretch belongs to visual arts—painting workshops called Montulika led by mentors like Lithuanian artist Gerda Liudvinavičiūtė, the acclaimed Assamese painter Noni Borpujari, and Debjani Hazarika, among others. Sculpture workshops run parallel, hands pulling shapes from clay in Monmrittika sessions. Then from January 15, music takes over. You hear Sa Re Ga Ma hummed across the property, vocal exercises mixing with river sounds, rough compositions polished under the guidance of musicians who have spent decades mastering their craft.

The inauguration on January 15 brought Upen Borgayan and Dr Jadab Borah from Uttar Kamalabari Satra, grounding the residency in tradition. Then came sarod maestro Tarun Kalita, followed by classical vocalist Mitali De whose sessions anchored the first day. By evening, Atanu Bhattacharya led sessions before participants scattered for personal mentoring and jamming with Joi Barua.

Joi Barua—composer, singer, songwriter who understands both the technical precision of studio work and the raw energy of live performance. His craft lies in creating music that moves between languages and genres with equal fluidity, whether composing for orchestra or stripping a song down to voice and guitar.

At Dekasang, he sat listening to a nineteen-year-old guitarist work through chord changes with the same attention he would give any collaborator.

"We didn't have access to anything like this growing up. I've always wondered how to really talk to the next generation about art," he said during a break between sessions. "Mongeet represents the whole Assamese philosophy, the spirituality that's survived here for centuries. I'm just happy to be part of giving back to a land that's ours."

The conversation turned to the algorithm problem—how Instagram followers now determine who gets hired, how visibility trumps quality, how the business pushes everyone toward sameness.

"I've been lucky to build a career where I don't have to think about those things much. When you work in Bollywood, those conversations find you. But you have to rise above them," he said.

"The real point is keeping your creative perspective open, not getting driven by numbers. I think the whole thing is the human factor of how you take this ahead, and the ones willing to walk ahead. You don't make good grades because you have talent. You make good grades because of commitment. And someone was asking how do you do this thing? At the root of it is love for what you do."

He explained the difference between studio and stage work like someone who has mastered both. "In the studio, nothing feeds you except your own mind. You're drawing from silence. On stage, you're feeding off the crowd—their energy, their mood, their anger or joy. These are two different disciplines which can exist within the same artist. You have to embrace both."

Day two began early with Mitali De at half past seven, followed by sessions with Arup Jyoti Baruah, then Adil Hussain on voice training. Santanu Rowmuria led afternoon sessions before Anurag Saikia took over.

Anurag Saikia showed up wearing a hoodie that said "Mental Health" across the back. Born in Moran, Assam, he is one of the youngest musicians to win a Rajat Kamal National Film Award. His work includes scores for Karwaan, Thappad, Article 15, and the wildly popular series Panchayat. Last year his song "Ishq Hai" from Mismatched won Best Title Track at the International Indian Film Academy Digital Awards.

But his most personal project is probably Project Borgeet—ancient Assamese devotional songs reimagined with an eighty-five-piece Macedonian orchestra and a choir from Shillong.

He stood at the back of a session, just watching. "When you're around people like Adil da, Joy da, Kaushik da, you either get mesmerised or you become a student again. Every time I meet them, I become a student."

The hoodie became a talking point.

"Everyone's started talking about mental health now, and we should be. There's nothing shameful about it. I've been through things, so I'm open about it."

The pressure young artists face today is crushing. Algorithms decide what is valuable. Follower counts determine careers. The race for visibility can erase the work itself.

"When I feel overwhelmed, I usually just take a break. Cut myself off completely, go somewhere else. Or I listen to more music, watch films. You have to be patient with yourself. Not every day is going to be your day."

What does he take away from Mongeet?

He laughed. "That's a trade secret. I never share it." Then he relented. "Okay, one thing. I'll meet someone here who's in Class 11. Their whole understanding of life, the slang they use, the music they listen to, what they watch and read—it's completely different from what it was for me or for Adil da. Talking to Adil da gives me one kind of inspiration. Talking to these kids gives me something totally different. I'm jealous of them, honestly. We had nothing like this. And I'm very much hopeful and confident that all of those participants are going to do crazy things in their life."

The question shifted to originality—what it actually means in a world where everything has been done.

"I think it's honesty. In music, there are only a few notes. Everything has been tried. There are maybe seven or eight core subjects that songs return to again and again—love, patriotism, loss. What makes your work different is honesty. Experience adds layers, sure. But the foundation is being honest."

One participant, still processing everything the past week had given her, said quietly: "I came here thinking I knew what I wanted to make. What I've learned isn't technique. It's permission—permission to trust my instincts, to take my time, to measure my worth by how true the work is instead of how many people see it."

Late afternoons disappeared into private practice. Musicians vanished with their instruments into corners. No performances or audiences, just the necessary space where bad first attempts evolved into better second ones, where creation happened before it became public.

Then evening arrived, and things got loose. Nobody scheduled the jam sessions. Someone started playing. Someone else jumped in. Suddenly, a folk singer was collaborating with a hip-hop artist, creating something that could not exist anywhere else. Mentors joined as fellow musicians, everyone exploring what happens when thinking stops and feeling begins.

One morning, Devajit Lon Saikia sat down for a conversation. The Secretary of the Board of Control for Cricket in India. Yes, that BCCI. At an art residency in the middle of Majuli.

"I've always loved cultural events. Drama, music, everything. Kaushik and I are both travellers, and whenever we'd meet during our trips, he'd tell me about what was happening with culture in Assam. He's a great storyteller," he said.

What he had witnessed at Mongeet impressed him. "What I have seen here is very interesting, how the young generations are inclined towards grooming them in the proper way to evolve as artists. So that is very interesting, and I am very confident that the new generations where there are so many distractions, this kind of workshop or this kind of sort of festival where a lot of mentoring takes place will definitely guide them on the right path."

He has brought artists to IPL matches in Assam and created entertainment segments as part of the cricket experience. "In the last three editions of IPL matches happening in Assam, we always have that entertainment segment, so in entertainment, I always invite the best of the artists from here to perform on a bigger stage," he explained.

During the Women's World Cup, he organised an hour-long tribute where he invited artists from across the Northeast. "These are important organs of the society; unless every angle, every component is taken well care of, it will be difficult for the society to grow, so we cannot leave any section secluded from the other part."

Does cricket have anything like this—something beyond regular training camps?

"Mongeet is definitely providing a lot of exposure and many insights into how cultural talent and the cultural quotient can be improved. In cricket, we have something similar, but it is done in a much more structured way. There are also some off-the-cuff or off-the-field activities, but these are mainly meant to keep the mind in the right shape and improve concentration in the game."

That evening on January 14, Adil cooked Qureshi mutton for everyone. The smell filled the property as participants gathered around, conversations flowing easily between mentors and students, all the hierarchies that govern the regular industry simply dissolving over food.

Every night brought a bonfire. Faces glowed orange in the firelight. Guitars got passed around. Participants sat next to National Award winners, and nothing mattered except the music and the fire and the river beyond and the shared understanding that this moment counted for more than any metric ever could.

Adil's frustration with cultural policy spilled out one afternoon. He does not think India has ever had a real cultural policy—not just the current government, but since independence. "We have a cultural agenda, but not a policy," he said, leaning forward. A proper policy would be drawn out, researched, investigated. It would help people understand the importance of art in human society.

The problem, he explained, is that art does not give instant gratification. People think it is leisurely, not essential. "That's the mindset, unfortunately. Those who rule our country—I don't think anybody understood what culture and art mean for human evolution."

His intensity built as he drew a distinction. "We had certain pundits—knowledgeable people. But we did not have gyanis, those who have applied that knowledge in life and become wise." India lacks wise people in policymaking, he argued. Without that perspective, without that vision, the country cannot understand how art can shape a society that is robust yet gentle.

"When we have to fight, we would fight—but not to hate somebody. We would fight with our lives, the way Krishna tells Arjuna. Our cultural policy should develop that human consciousness."

He pressed the point harder. "All this talk about becoming Vishwa Guru will go down the drain if we lose our humanity, our profound understanding of who we are." That understanding, he said, was given by the greatest Rishis and Maharshis—from ancient times through Sri Aurobindo, Ramana Maharshi, Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, Vivekananda, Sankardev. "If we don't follow that, we become like the thugs we're fighting. If I hate you because you're hateful toward me, I become hateful. That person has succeeded. They've made me inhuman."

The problem Mongeet addresses is simpler but equally urgent. Before social media, it was parents, teachers, peers who influenced what young people should do. Adil described growing up in a suppressive society where people were not encouraged to do what they felt like doing. "We paid the price for that."

Then social media arrived and exponentially dominated choices. "What's trending, how many views, how many likes—we saw everybody trying to sound like Zubeen or Papon." Mongeet, he explained, is for people who want to explore what they actually want to do. "We wanted to give them courage, to take them through a process so they can trust themselves and find their own voice."

The evening of January 16 brought something special during Golpo Kotha, the storytelling session. Everyone gathered in Guru Griha, the line between mentor and participant disappearing completely. Atanu Bhattacharya told two stories, including one about a miser, his voice rising and falling with the narrative. As he spoke, classical vocalist Mitali De wove in musical interludes—classical notes that added melody and drama to the tales, her voice humming various ragas between passages. At the end of the second story, she hummed "Jeena Isika Naam Hai"—that old Hindi film song—but threaded through with classical inflections that transformed something familiar into something transcendent. Sa Re Ga Ma Pa became a meditation, a reminder that music exists to be felt in your bones, not consumed like content.

The morning of January 17 began with Arupjyoti Baruah at half past seven, followed by intensive workshops led by Anindita Paul and Rupam Bhuyan. Rupam, a respected figure in Assamese music, worked with participants on arrangement and composition, while Anindita focused on vocal technique and stage presence. After that, participants scattered to individual mentors for private sessions—the kind of one-on-one teaching where you might spend twenty minutes working through a single musical phrase or brushstroke, where the deepest learning often happens. By afternoon, everyone had left for Sonapur.

The Brahmaputra gives and takes with equal indifference. Majuli has lost two-thirds of its landmass since the 1950s. Villages vanish. Satras relocate. This island, fighting for its survival, hosts a residency fighting for artistic survival. Kaushik built Dekasang anyway—near the river, on sand and faith.

The ferry crossing back happened from Dhulaguri this time, a different ghat than the one used to arrive. Same river, different angle. The water still churned blue and massive, indifferent to the transformations happening on its banks. Young artists had discovered their voices over these days. Mentors had given without keeping score. That particular chemistry had occurred—the kind that happens when ego dissolves, and only the work remains.

After those ten days in Majuli, Mongeet moved to Dekasang Sonapur near Guwahati. January 18 brought sessions with Bipuljyoti Saikia and Sasanka Samir, followed by Shankuraj Konwar, then Kalyan Baruah, and DJ Phukan. January 19 saw Shashwati Phukan, JP Das, Umananda Duara, and Abani Tanti leading sessions. Then on January 20 came the culmination—the performances, with morning sessions led by Dipen Baruah and Pulak Banerjee.

Participants went first, performing the original compositions they had worked on for ten days. Everything they had learned, everything they had discovered about their own voices came together on stage. The audience—full of people who could critique every technical flaw—listened with the kind of attention that only comes from genuine respect.

Then the mentors performed separately, demonstrating what decades of commitment looks like. Joi Barua, Pulak Banerjee, JP Das, Kalyan Baruah, Shashwati Phukan, Shankuraj Konwar—each brought their mastery to bear.

But one moment broke through the usual separation between mentor and student. Shashwati Phukan sang one song with former Mongeet participants, a tribute to the late Zubeen Garg. The song was "Mayabini." Other former participants performed renditions of Bhupen Hazarika and Zubeen Garg, their voices carrying the weight of tradition while searching for their own expression within it.

Funding this remains a challenge. "The government helps some—Oil India, State Bank of India, Rajasthan Royals, a few other companies. But mostly Adil and I are covering costs ourselves. Having it at our resort helps," Kaushik explained. "These thirty-five songs each have three or four participants—someone writing, someone singing, someone composing. That's at least seventy to eighty people showing up, some with their parents. It becomes huge."

For people who applied but were not selected yet still want to attend, Kaushik offers an option: "We tell them we're sorry they can't participate officially, but if they want to join the residency anyway, they can pay five hundred rupees a day for accommodation and five hundred for food. A thousand total. We can definitely fit them in."

The whole setup is deliberately intimate. Everyone sits on the ground. "It's that guru-shishya feeling, like a gurukul. Majuli has satras—Vishnu monasteries—that have been practising these traditions for five hundred years. We're trying to absorb the best parts of what they've learned about art, architecture, music, dance, and food. All of it together creates the ecosystem."

Adil is blunt about the financial reality. "Art residencies don't attract corporate sponsors. They don't generate TV ratings. We're urging everyone who values this work to come see what we're doing with the resources, to support it financially if they believe in it."

The conviction in his voice carries weight: "Every young artist who leaves here carries something forward—the courage to create something original, something real. That's what we're fighting for. Not against the algorithm, but for the human voice underneath it."

Somewhere on that island, in the foundation built in memory of a young man who died saving his friends, next year's participants are already composing songs they do not know they will sing. Already sketching images they have not seen yet. Already learning to trust that their voice—specific, unrepeatable, theirs—matters.

Because at Mongeet, for ten days every January, it absolutely does.

Copyright©2026 Living Media India Limited. For reprint rights: Syndications Today