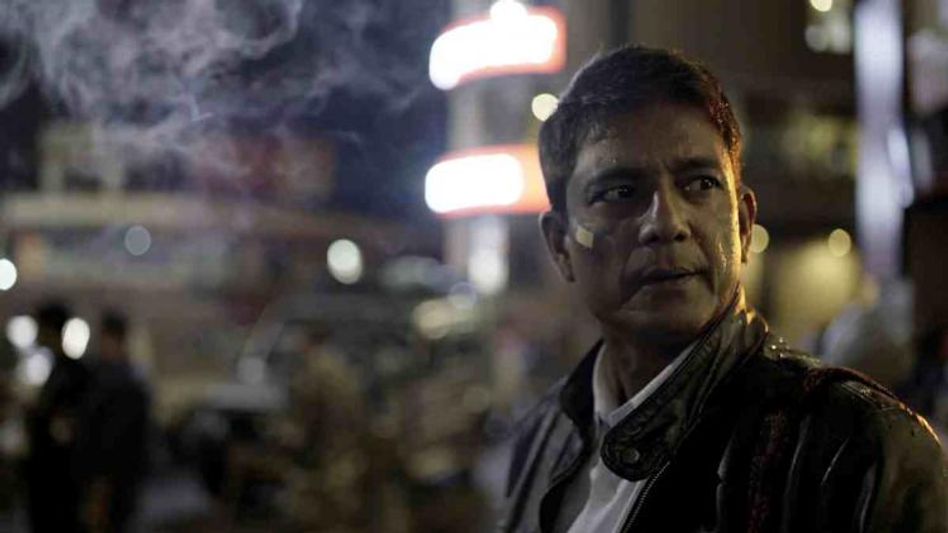

Adil Hussain's character in 'Lorni-The Flaneur' mirrors Shillong's 'close-knit cultural identity

Adil Hussain's character in the feature film transforms himself into a detective in an effort to escape the boredom and frustration of his dull lifestyle

Adil Hussain, Actor

Adil Hussain, ActorLorni- the Flaneur, a Khasi movie that encapsulates the soul of Shillong is now all set to premiere on SonyLIV on September 2. Adil Hussain's character in the feature film transforms himself into a detective in an effort to escape the boredom and frustration of his dull lifestyle.

Our Khasi Film @TheLorni is premiering on @SonyLIV on the 2nd Sept . I play the protagonist, a small town Detective, in this very intriguing story, set in #Shillong #Meghalaya directed by @WanphrangD https://t.co/9FsSWZevkg

— Adil hussain (@_AdilHussain) August 29, 2022

Attuned to the pulse of the streets, he is unexpectedly assigned a mission to look into the "disappearance of things of great cultural value". And there begins a thrilling journey through his sleepy small town's night-time roads and passageways, which also serve as a metaphor for Hussain's chaotic thoughts.

Wanphrang K. Diengdoh, Lorni's director, is the founder of 'Reddur", a film and music production facility. He is also a member of the political punk band Tarik and the 'Khasinewave' music project 'Nion'. His debut short film, '19/87', won every award at the Guwahati International Short Film Festival in 2011.

What does the 'Lorni' word signify and how does it relate to Shillong?

‘Lorni’ is a Khasi word that has no other translation in any other language. It is a word that best describes a connection that close-knit communities have with a place and the people who inhabit that place. Having grown up in Shillong, I could not resist working on characters that truly reflect and mirror this identity.

How did you end up selecting the role of the protagonist on Adil Hussain?

Voodoo and black magic, just joking. I reached out to Adil because I wanted him to mentor the actors we had selected in Shillong. I was keen on getting the characters to play their roles ‘truthfully’ and not ‘act’. It sounds easy but it is the most difficult thing to do if one isn’t a trained actor from a certain school of thought. He asked for the script and then he reached out to me and said he was keen to play the lead in the film. I told him straight up that I couldn’t afford him and his response will forever resonate in my thoughts whenever the going gets tough. He said, “This is for the sake of art”. Now I am a musician and I have heard that being said ten million times already in conversations all across Shillong and a part of me did go, “Yeah, right!” but I told my cynicism to take a hike because when someone like Adil Hussain says it, it definitely comes from years of experience, honesty and also reestablishes your faith in your profession.

I told him I anticipated a 30-day shoot in total, including his sequences. Adil said he would give me 15 days for his sequences. I shot his bits in 14 days and on the 15th day got him to do a one-take music video, on a moving scooter, synced to live music! And why not?

Also, Adil is a fine actor, in fact, one of the best actors in the world today if you were to ask me. I have interviewed a wide range of characters for my documentary films and I understand the blurry lines between performance, reality, the camera, and the observer. Adil understands all of those nuances extremely well and it is very easy for me to communicate to him my expectations as a director.

Also, what is encouraging for the people of our region is that he would always acknowledge Goalpara without romanticizing it no matter where he is in the world; perhaps the same way that I would always acknowledge Shillong in my works. Most importantly, he is a humble human being and has a fantastic aura and energy which make working with him an absolute pleasure.

Did you shoot the film solely in Shillong, or did you use other locations as well?

We shot the entire film in and around Shillong in locations with faces that sometimes escape glossy coffee table books and aerial photographers. I was very keen to represent the place as it was and I wanted people to almost smell the film, to arrive at this so-called elusive poetic and ecstatic truth. I wanted it to be a documentary without it being a documentary and all those years working in guerilla filmmaking situations in actual locations and understanding that the non-fiction format and the fiction format are the same has finally paid off.

Can you tell us about your filmmaking journey?

It all started when I got hold of my first camcorder when I was about 16 maybe? This was a time when video technology and cameras were becoming more and more accessible and no longer required an exorbitant amount to procure one. I walked around town filming pretty much everything I found intriguing. And then I enrolled in a local media college after a Bio-technology stint that went a little awry.

I spent copious amounts of time moving around Shillong hanging around at different tea shops observing the clientele there or bumming around at friends listening to albums on repeat in a haze of confusion seeking a sense of self and personal identity or wandering on the same stretch of road because honestly there was not much to do in Shillong back then.

After my graduation, I would then land in Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi to do an MA in Mass Communications. But even here, I was anxious to leave and start making my films, not because I did not like the course but because I couldn’t wait to start telling my own stories. My MA graduation would also coincide with the financial collapse of 2008 which meant that the gradual and predictable progression of Jamia graduates toward NDTV came to a halt because all the interns and fresh apprentices at major production houses and big businesses were being made redundant. It was also a point of time that saw Delhi’s urban and sub-urban landscape going through a massive transformation because of the Metro and other activities geared toward the Olympics in 2010. This meant that the city became a dusty labyrinth of construction work that witnessed the arrival of migrant labourers from all across India seeking employment opportunities. I had just purchased a DSLR then and moved around the city photographing this transformation and this was a period that saw publishing houses in India churning out a lot of graphic novels. I remember reading Parismita Singh’s, ‘The Hotel at the End of the World’ and telling myself, “Hey, I want to make a graphic novel too”. And I did. I got myself a piece of DIY glass and light setup to trace drawings, a rickety scanner, and an even ricketier chair and started working on my graphic novel- a surreal, film-noir with lenient doses of Khasi humour, legends, and anecdotes that situated itself in and around Shillong. There was a significant amount of work done on it to be fair but eventually, the Delhi noise and the dust compounded with the confusion and anxieties of a Khasi middle-class child meant that I was ready to come back home. But as a parting gift, Delhi was also kind to me. I received a grant from the Foundation of Indian Contemporary Arts for an installation called ‘Kali Kamai’ that examined local taxis in Shillong as public spaces. It was great because it gave me something to do in Shillong with all that politically charged idealism and angst that I had gathered from Delhi. It would also coincide with a time when I directed my first feature film ‘19/87’ with Dondor Lyngdoh and Janice Pariat- a 36-minute historical fiction about a Muslim tailor with the gift of prophecy and his friendship with a Khasi chap. It was a great learning experience and we sent the film to a film festival in Guwahati in 2011 where it won pretty much all the awards. Sadly, we were never paid by the festival team. I wonder where they are because I really wouldn’t mind the cash prize actually (with an interest please, thank you very much).

And then shortly after our first film, I received the ‘Early Career Film Fellowship’ from TISS, Mumbai in 2013 for my documentary proposal ‘Where the Clouds End’- a film on the Inner Line Permit issue and ideas of purity and border politics. The film premiered at the Cinema Room in the World Urban Forum (WUF) 7 in Medellin, Colombia, and thus began my journey with the non-fiction format in 2017 after having researched, written, directed, shot, and edited ‘Because We Did Not Choose’, a film on the participation of labourers during the First World War. To call the film, a labour of love would be a mere understatement.

How your Filmmaking journey led to the development of this film?

‘Because We Did Not Choose’ premiered at the Nehru Centre, London, and shortly after that I needed a break I went back to my drawing room and it was almost as if the graphic novel story was leaping out from the shelf and screaming out at me, “Me, me, me. I am next”. I skimmed through the pages and I knew this was it. I am going to make my first Feature Fiction, ‘Lorni-the Flaneur’ come what may. I decided to take a break before I dived into the project and landed up in Goa for a holiday. But I was sucked into this frenzy because the characters from the graphic novel did not leave my thoughts and my mind was pregnant with all these characters. It was almost as if they were talking to me already and I could now see who they were. How could I possibly stop myself from writing the screenplay then? And so I did, and the holiday became this strange visitation of these creative muses and in a couple of weeks, I finished the first draft. The rest of course is history as they say.

In the film, a detective investigates the disappearance of objects worthy of great cultural value, what is the motive behind this?

All ideas are hypothetical and are governed by the relative logic that drives them forward. The disappearance of the objects is a metaphor for the confusion of a minority community in an era of homogenized identities- to remember but also at the same time to not romanticize or blindly follow a past without questioning our histories. And also, of course, a metaphor that best represents a time and space from where I come from.

Copyright©2025 Living Media India Limited. For reprint rights: Syndications Today