Apatani: The tribe of Arunachal where womenfolk want to look ugly

In the heart of Arunachal Pradesh, nestled within the serene landscapes of Ziro Valley, resides the Apatani tribe, a community that stands as a testament to the rich tapestry of human culture and its myriad expressions.

In the heart of Arunachal Pradesh, nestled within the serene landscapes of Ziro Valley, resides the Apatani tribe, a community that stands as a testament to the rich tapestry of human culture and its myriad expressions.

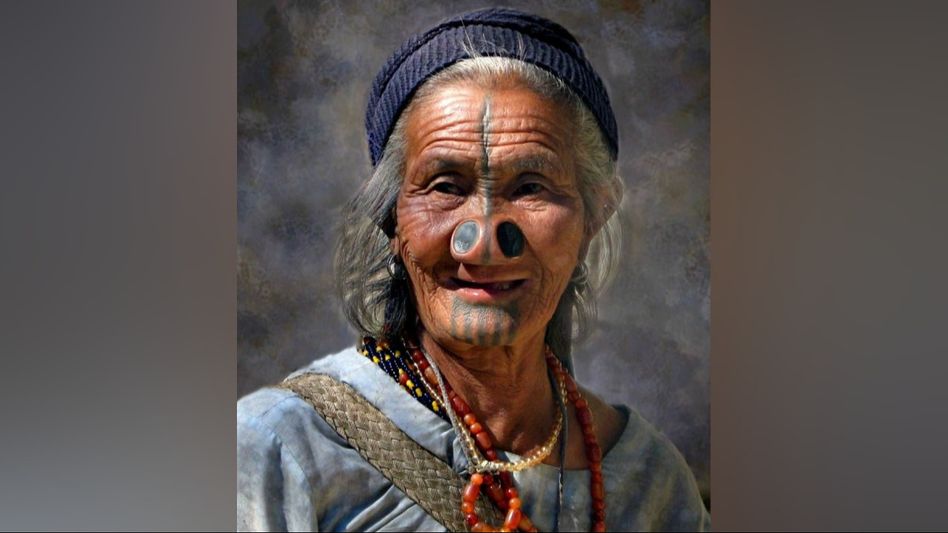

This tribe, one of India's last remaining pagan societies, is distinguished not only by its shamanistic traditions but also by the unique and striking facial decorations of its female elders. These adornments, comprising large wooden nose plugs known as yaping hullo and intricate facial tattoos called tippei, are emblematic of the tribe's identity and womanhood.

The origins of these peculiar beauty standards trace back to a time when Apatani women were renowned across the valleys for their unparalleled beauty.

This allure, however, became a double-edged sword, as it led to men from neighboring tribes kidnapping Apatani women. In a bid to protect their women from such fates, the Apatani men conceived the idea of altering their women's appearances to make them less appealing to outsiders.

Thus, the practice of facial tattooing and the insertion of nose plugs began, with elder women tattooing young girls as soon as they reached ten years of age.

These modifications, while initially intended to deter, evolved into symbols of identity and pride for the Apatani women.

The dark vertical lines of the tippei, a mix of pig’s fat and soot, and the wooden plugs, sourced from the forest and sterilized in fire, came to represent the main features of the tribe’s womanhood.

However, the advent of Christianity in the early 1970s, brought into the valley by missionaries from South India, marked the beginning of the end for these practices. The new religion and modern beauty standards deemed the marks incompatible, leading to a decline in their prevalence. Today, only a last surviving generation of Ziro women bear these marks, a poignant reminder of a fading tradition.

Despite the changes brought by time and external influences, the Apatani culture remains resilient. The tribe's animistic and shamanic ancestral religion, Donyi Polo, meaning "Sun Moon," continues to thrive, with white flags emblazoned with a red sun fluttering atop most buildings in Hari, one of the Ziro Valley’s eight Apatani settlements.

This religion, which grew stronger in the 1970s as a form of resistance against the arrival of missionaries and the push to embrace Hinduism, is a testament to the tribe's enduring spirit and commitment to preserving their identity.

As the world encroaches upon the secluded valleys of Arunachal Pradesh, bringing with it the inevitable forces of change, the Apatani tribe stands as a beacon of cultural preservation.

Their practices, though misunderstood by many, offer a window into the complex interplay between beauty, identity, and survival. In the face of modernity, the Apatani women, with their yaping hullo and tippei, embody the resilience of a culture determined to maintain its essence amidst the tides of change.

Copyright©2026 Living Media India Limited. For reprint rights: Syndications Today