Study links gut immune cells to spread of Parkinson’s to brain

Researchers identify gut immune cells as key players in Parkinson’s disease spreading to the brain. This breakthrough could lead to new treatment approaches targeting these cells

A study by researchers at University College London has identified how immune cells in the gut may help Parkinson’s disease spread to the brain, opening up a potential new target for treatment.

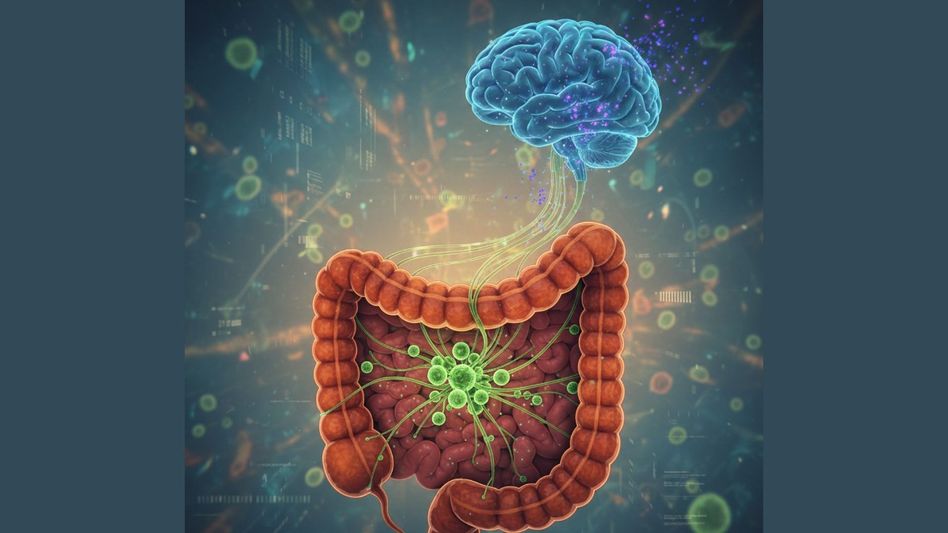

Parkinson’s disease, a neurodegenerative condition marked by tremors, stiffness and slow movement, is increasingly thought to begin outside the brain. One of the earliest brain regions affected is the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve, which has a direct connection to the gut. Until now, however, the precise route by which the disease spreads to the brain had not been clearly understood.

The study, conducted in mice and published in the journal Nature, shows that gut macrophages — immune cells that normally destroy pathogens — play a central role in transferring toxic proteins from the gut to the brain.

Researchers found that reducing the number of these gut macrophages limited the spread of the harmful proteins and led to improved motor symptoms in mice with Parkinson’s-like disease.

Co-lead author Tim Bartels, a group leader at the UK Dementia Research Institute based at UCL, said neurodegenerative diseases develop slowly, often over decades. “Understanding how Parkinson’s begins in the body could allow us to develop simple blood tests to screen for it, enabling diagnosis long before damage to the brain starts,” he said. “Having the ability to detect and manage Parkinson’s before it even reaches the brain could have a huge impact for those affected.”

Previous studies have shown that people with Parkinson’s often experience gut-related symptoms, such as chronic constipation, many years — sometimes decades — before movement problems appear.

In the latest research, scientists isolated alpha-synuclein, a protein linked to Parkinson’s, from the brains of people who had died with the disease. Small amounts of this patient-derived protein were then introduced into the small intestines of mice, allowing the team to track how it moved from the gut to the brain.

The researchers observed that gut macrophages consumed the alpha-synuclein protein but developed faults in their lysosomal systems, which are responsible for breaking down cellular waste. These dysfunctional immune cells then signalled T-cells, another part of the immune system, to travel from the gut to the brain.

When gut macrophages were depleted before the protein was introduced, significantly lower levels of the toxic protein were later found in the brains of the mice.

The findings suggest a possible therapeutic approach focused on targeting immune cells and preventing them from carrying disease-related proteins to the brain.

Co-lead author Dr Soyon Hong, also a group leader at the UK Dementia Research Institute, said the results challenge the idea that immune cells play a passive role in Parkinson’s. “Our study shows that immune cells are not bystanders in Parkinson’s; these gut macrophages are responding, albeit in a dysfunctional way,” she said. “This presents an opportunity to think about how we can boost the function of the immune system and these cells, so that they respond in the correct manner and help to slow or stop the spread of disease.”

Copyright©2026 Living Media India Limited. For reprint rights: Syndications Today