Manipur’s Opium Crisis at Breaking Point

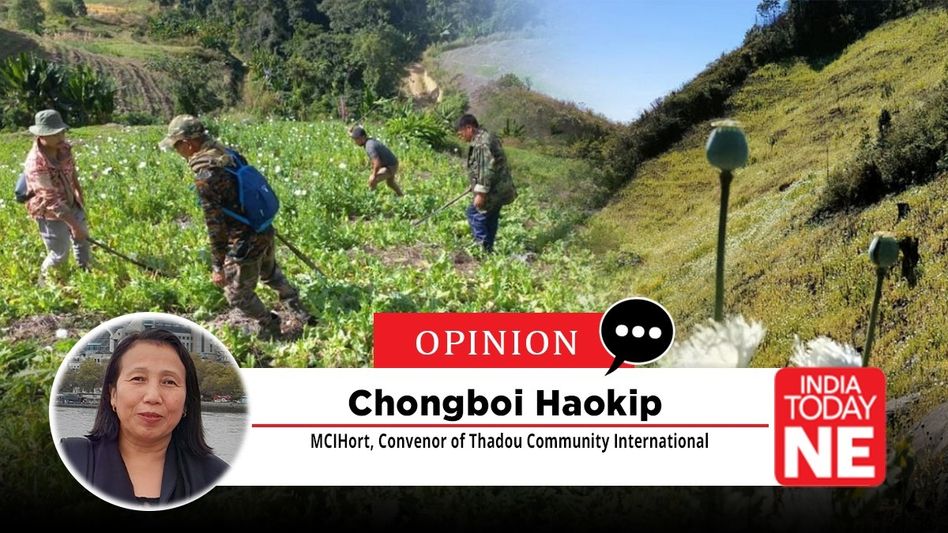

As morning breaks, Manipur's poppy fields expose families with no good choices. For many, growing opium (the dried latex from the seed pods of the opium poppy) means survival but also deeper poverty and fear. It is not about crime or greed. It is about desperation, about rural families forced to choose between the law and feeding their children.

As morning breaks, Manipur's poppy fields expose families with no good choices. For many, growing opium (the dried latex from the seed pods of the opium poppy) means survival but also deeper poverty and fear. It is not about crime or greed. It is about desperation, about rural families forced to choose between the law and feeding their children.

Though I was born and raised in Imphal, my ties to the hill communities remain strong. In speaking with those who live this struggle, I could empathise with why the opium poppy has become a silent killer across Manipur's most vulnerable regions. In these forgotten corners, the moral question is brutally simple: do you break the law, or do you watch your children starve while staying within it?

Case Study - Two Worlds of Opium Farming

Not all opium cultivation is the same. The first category operates like organised crime, i.e., well-funded networks that treat poppy farming as a lucrative enterprise, using it to accumulate wealth, control territory, and often to fuel violence. These operations are deliberate, calculated, and thoroughly criminal in intent.

The second group is different. These farmers are trapped in poverty, growing opium because they have no other option. Today's focus is on one such man, " Mr. X," who represents many across Manipur's hills. Before dawn, he walks through rows of poppy plants on his hillside field.His blade scores the green seed pods with practiced precision. White resin wells up and begins to dry in the cool morning air. By evening, he will scrape it off and sell it. The money will buy rice for his children, pay a fraction of what he owes moneylenders, and keep his family alive for another few weeks.

Mr. X knows this is illegal. He knows police raids could destroy everything he has grown. But he also knows that planting rice or maize will not save his family from hunger. "What else can I do?" he asks, his voice quiet and resigned. "We cannot eat promises." It is not a crime story. It is a survival story, and Mr. X is far from alone!

The Trap of Poverty

Across the hills of Manipur, thousands of subsistence farmers face the same impossible choice. They once cultivated rice, maize, and vegetables, providing for their communities and sustaining themselves from the land. That way of life is collapsing. Infrastructure in these remote areas is scarce. With no irrigation, farmers rely only on rain. One dry season can destroy an entire year's harvest. Broken or missing roads make it hard to move perishable crops before they spoil.

For families already living on the edge, these uncertainties are devastating. When a harvest fails or prices collapse, they borrow money from local lenders at crushing interest rates. Debt accumulates, hunger deepens, and with each failed season, the trap closes tighter.

Opium offers a way out, or at least it appears to. Opium buyers reach villages that food traders avoid. They pay in cash, on the spot. There is no delay, no haggling, no risk of crops spoiling on bad roads. For a farmer in debt, with hungry children and a failed rice harvest, opium is not a crime, but a survival taking high risks.

The Price Paid in Silence

The immediate cash from opium cultivation masks deeper costs that compound over time. As more land shifts from food crops to poppies, villages produce less of what they need to eat. Families that once grew their own rice now must buy it at market prices. The money earned from opium gets consumed by food purchases. What appeared to be income turns out to be a deception. Families remain poor, but now they are also dependent on an illegal economy and more vulnerable than before.

Children inherit this vulnerability. They grow up surrounded by addiction and criminal networks, with almost no future options. Schools are substandard or even being closed. Many children spend their days in the fields beside their parents, learning only one trade: how to grow an illegal crop. The cycle prepares to repeat itself.

Why Punishment Fails

Current policy on opium poppy by law enforcement (often) is not a solution. Fields are destroyed, and cultivators could be arrested. But this approach only fundamentally misunderstands the situation. It punishes poverty rather than addressing it. The poor farmer pays the price while the profiteers walk free.

A field destroyed this season will likely be replanted with poppies next season if the farmer has no other way to survive. An arrest may remove one cultivator, but it does not remove the poverty, debt, and lack of alternatives that drove him to opium. It simply transfers the burden to his family, making their situation even more desperate.

Without intervention that addresses the root causes, such as poverty, debt, inadequate infrastructure, and the absence of markets for legal crops, the crisis will continue to expand. The scale of cultivation has grown significantly in recent years, drawing more villages into the cycle. The longer this continues, the harder it will be to reverse the point of no return.

What Real Support Looks Like

Breaking the cycle demands a shift from punishment to support, from raids to development. Farmers must be given tangible ways to survive without opium, and those options must be practical, lasting, and financially secure.

Stable markets for food crops are essential. Farmers need guaranteed minimum support prices for rice, maize, and vegetables. When farmers know they can sell their harvest at a fair price, regardless of market fluctuations, they gain the confidence to invest in food and alternative high-value crops. This single measure could transform the calculation that drives farmers toward opium poppy.

Infrastructure investment is fundamental to viable legal farming. Irrigation reduces dependence on unpredictable rainfall, while storage facilities prevent crop losses during harvest. Roads provide access to broader markets, competitive prices, and diverse buyers - these are essential foundations, not optional additions.

All-weather roads are especially critical. In fact, cost-efficiency must align with long-term durability. As reported by India Today NE on October 1, 2025, former Chief Minister N. Biren Singh urged the construction of durable and safe roads. He pointed out rightly the need for quality roads in terrain already burdened by severe logistical and weather challenges.

Community-led livelihood programs must be designed in collaboration with the villages themselves. Alternative crops, such as ginger, turmeric, or fruit trees, may be viable options, but only if supply chains and markets are established for them. Programs imposed from outside without local input and without guaranteed buyers will fail.

Debt relief tied to commitments for alternative crops can help farmers escape the cycle of borrowing at high interest rates. Microcredit schemes with fair rates can provide capital for small businesses or non-farm activities, creating economic opportunities that extend beyond cultivation.

Healthcare and education provide communities, especially children, with a pathway out of poverty. Villages locked in the opium cycle often lack basic services.

On a Positive Note

It is encouraging, as reported by the Sangai Express (Epao, April 28, 2025), Mr. K. Debadutta Sharma, Director for Horticulture and Soil Conservation said that the Manipur government has constructed a cold storage in Churachandpur district, which is under the poppy-growing belt. There must be government facilities that we can utilise effectively and that are in the pipeline, which would help our target poppy farming group, who need support. The community must work in cooperation with the government to pursue the common good.

A Question That Still Hangs

As Mr. X walks back from his field, the container of opium resin heavy in his hand, he does not think of profit. He thinks of how many days of rice this harvest will buy. He thinks of the debt collectors who will soon knock on his door. He thinks of his children and whether they will ever see a life beyond the poppy fields.

Manipur's opium crisis has reached a breaking point. But this crisis is not beyond repair. With political will and sustained investment, we can break the cycle with collective effort. The government can provide farmers with alternatives that actually support them. Villages can return to food crops.

For that to happen, the state must act with both compassion and vision. Farmers must be seen as citizens in need of support, not as criminals to be punished. Real change will come not from raids, but from roads; not from arrests, but from assured markets; not from destroyed fields, but from rebuilt livelihoods. As a community, we could explore ways to support these farming groups in breaking free from their bondage and creating a win-win situation for all. Let us build mutual trust, nurture it and give hope the power to win against all odds!

It reminds us of Martin Luther King Jr.'s saying, "Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere."

About the author:Chongboi Haokip, MCIHort, is an international development consultant specialising in Agriculture, horticulture and trade facilitation. She can be reached at chongboi4community@gmail.com.

Copyright©2025 Living Media India Limited. For reprint rights: Syndications Today