Bangladesh Election: Jamaat–NCP surge near India’s border raises security concerns

Jamaat and the anti-India NCP have tightened their grip along Bangladesh’s border with Assam and Bengal, unsettling India’s security calculus. Experts urge vigilance, not panic but warn that polarised politics and neglected frontiers could slowly turn electoral gains into strategic risks.

The outcome of Bangladesh’s 2026 general election has travelled swiftly across the riverine frontier into western Assam. In districts like Dhubri—where the Indo–Bangladesh border is not an abstraction but a daily administrative reality—the verdict is being read less as distant politics and more as a strategic signal.

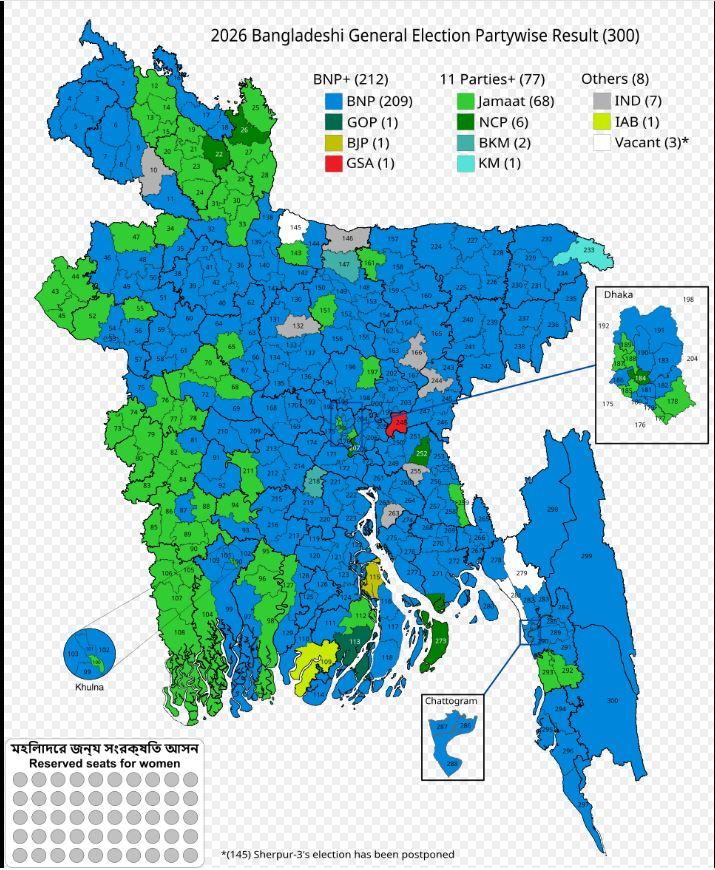

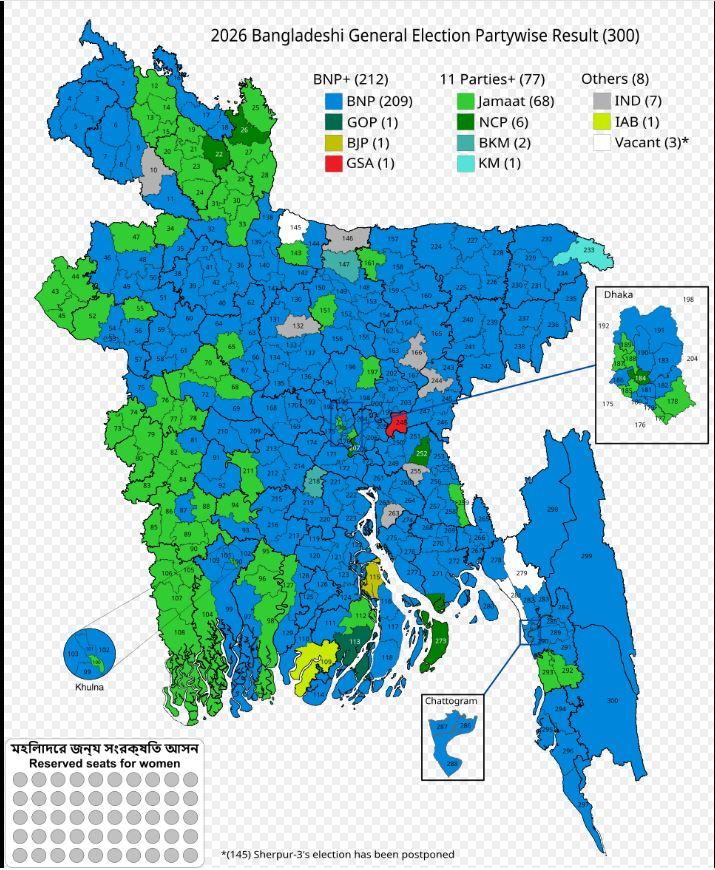

Nationally, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) has secured a sweeping two-thirds majority. Yet in the northern districts adjoining India—particularly Kurigram and Gaibandha—the Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami (Jamaat) and staunch anti-India party National Citizens Party (NCP) have significantly expanded their parliamentary footprint.

That contrast—BNP dominance at the centre and Jamaat consolidation in parts of the north—has sharpened anxieties along Assam’s 263-kilometre frontier segment. In fact, Jamat has also done exceedingly well in the constituencies along the West Bengal border.

The Northern Numbers and Their Optics

In Kurigram, adjacent to Assam and Meghalaya, Jamaat won three of four parliamentary seats. BNP failed to secure a seat there. The remaining constituency went to the National Citizen Party (NCP). This is the same party whose leader, Hasnat Abdullah, had warned that if India attempts to destabilise Bangladesh, the party might support forces aiming to sever India’s “Seven Sister” states, a statement widely considered provocative.

In neighbouring Gaibandha, Jamaat captured four of five seats, with BNP narrowly winning only one. The pattern reads like a north-belt consolidation. BNP’s overall vote share may remain competitive nationally, but in this terrain, Jamaat converted support into seats with striking efficiency.

When mapped against Assam’s Dhubri–Kurigram stretch, marked by unfenced riverine patches, erosion-prone chars, cattle smuggling routes, and documentation drives, these numbers acquire symbolic weight.

Optics matter on sensitive frontiers. Yet optics are not evidence.

Security Lens: Vigilance Without Alarm

Former Assam DGP Bhaskar Mahanta situates the outcome within institutional continuity rather than rupture: “A decisive BNP mandate prevents the kind of uncertainty that breeds administrative paralysis — and vacuums exploited by non-state actors. For Assam’s sensitive frontier, this reduces the immediate risk of instability spilling over. This was a political shift — not a fundamentalist takeover.”

Former SSB Special Director General Jyotirmoy Chakravarty adds historical context. “Jamaat has historically aligned with BNP governments without commanding decisive leverage. It was an ally since 1996, joined the cabinet in 2001 with 14 seats, but remained limited in stature. Its registration was declared illegal in 2013 and restored in 2025 under conditions. The current rise, he argues, must be read within that legal and historical continuum—not through alarmist lenses.”

Lt Gen Rana Pratap Kalita, former GOC-in-C Eastern Command, introduces a more granular strategic reading. “Jamaat performed strongly in rural and border districts by leveraging grassroots networks and latent anti-India sentiment. Urban voters, women, and youth appear to have shown relative resistance,” he says.

He notes that sections of border populations often perceive India’s border management practices—fencing, surveillance regimes, cattle seizures, and mobility restrictions—as disruptive to traditional cross-border socio-economic patterns. Jamaat, he suggests, capitalised on those sentiments.

The risk, in Kalita’s assessment, is not immediate destabilisation but gradual exploitation. A strong ideological footprint in border districts could be leveraged by extremist elements, potentially encouraging illegal migration, social friction, and propaganda narratives.

The re-establishment of camps by Indian insurgent groups inside Bangladesh, historically witnessed in earlier decades, cannot be dismissed outright, though there is no current evidence of such revival, he said.

His prescription is calibrated: heightened surveillance, robust border management—preferably coordinated with Bangladeshi forces—and diplomatic pragmatism. The trajectory will depend on how Dhaka balances domestic political compulsions with bilateral ties.

According to Chakravarty, Jamaat’s rise should be viewed through its legal and historical trajectory rather than through an alarmist lens. Over the next 10 to 20 years, he believes, the party is likely to remain largely focused on domestic politics. Its future influence will depend on how the BNP governs and how India calibrates its Bangladesh policy. He also cautions that growing religious polarisation in India could inadvertently strengthen Jamaat’s anti-India narrative, creating political space for its expansion.

Mahanta struck a distinctly pragmatic note. He argued that fears of a Jamaat surge along the Assam and Bengal border belts were overstated, pointing out that the data reflected only localised pockets of support rather than a nationwide extremist wave. What had occurred, he said, was a political realignment, not a fundamentalist takeover.

Assam must stay alert, especially in unfenced riverine stretches. Policy must be driven by preparedness, not political rhetoric. Technology matters, but strengthening the “human fence” through trusted border communities is decisive. They are the first line of intelligence. Bottom line: Vigilant borders. Firm security. Pragmatic diplomacy.

The thread linking all three security perspectives is clear: preparedness, not panic.

The Narrative Risk Inside Assam

If there is a proximate risk, it lies less in cross-border movement and more in narrative spillover.

Assam’s politics, particularly in districts with substantial Muslim populations, is already sensitive to identity discourse. Amplified rhetoric framing Kurigram’s verdict as ideological consolidation along the frontier could deepen suspicion within border communities.

In contemporary contexts, radicalisation often feeds not on infiltration but on grievance accumulation and polarised messaging.

An atmospheric shift is more plausible than a kinetic one.

Dhaka’s Messaging and Diplomatic Signals

Adding complexity is post-election commentary from senior BNP adviser Humayun Kabir, who called for “balanced relations” with India while flagging concerns over what he described as rising “Hindu extremism” in parts of Indian society. He framed radicalisation as a broader South Asian phenomenon, arguing that Bangladesh’s situation is “not at that level.”

Such articulation suggests Dhaka intends to recalibrate ties from a position of parity rather than deference. Yet it also implies continuity in counter-terror cooperation and intelligence sharing—pillars that have stabilised the frontier over the past decade.

The institutional architecture of India–Bangladesh security cooperation remains intact.

The Larger Calculation

Geo-politics operates on longer arcs than electoral cycles. India–Bangladesh relations have survived ideological shifts before. Trade corridors, transit routes, river-water management frameworks, and coordinated border mechanisms create structural interdependence.

Jamaat’s northern gains are a political fact. Whether they mature into a security concern will depend less on the ballot and more on governance choices in Dhaka, diplomatic calibration in New Delhi, and rhetorical restraint in Assam.

There is legitimate concern, but no immediate cause for alarm. Border stability is not shaped by headlines; it is sustained by institutions. The quieter the discourse, the steadier the frontier.

(Mrinal Talukdar is a Distinguished Fellow at Gauhati University and an author-journalist)

Copyright©2026 Living Media India Limited. For reprint rights: Syndications Today