Bridges rise, prejudice remains: Northeast and India’s unfinished union

India is finally racing to connect the Northeast with tunnels, bridges and rail lines, yet its people are still forced to justify their belonging with their last breath. The killing of Anjel Chakma exposes a brutal paradox: a region embraced on paper and on screens, but resisted in everyday conscience.

Imagine being killed in your own country for who you are—and having to say, “I am an Indian.” That sentence alone explains why the last few days have been so overwhelming for the people of the Northeast, coming as they do at a moment when the region has abruptly moved into national focus.

After decades of being overlooked, infrastructure announcements, cultural visibility, tourism figures and popular media references are arriving almost simultaneously. For a region long accustomed to absence rather than attention, this moment feels less like recognition and more like a cautious reckoning.

The scale of recent development is hard to miss. There are initiatives to position the Northeast as an attractive destination for investors and tourists. Landmark projects like as the Sela Tunnel in Arunachal Pradesh (situated at an altitude of 3,000 metres, provides all-weather road connectivity between Guwahati in Assam and Tawang, stretching 13,000 feet, making it the world’s longest two-lane tunnel) and the Bhupen Hazarika bridge (Dhola-Sadiya Bridge, officially named the Bhupen Hazarika Bridge, is a beam bridge linking the villages of Dhola and Sadiya in Assam’s Tinsukia district) in Assam have reshaped connectivity.

Over 11,000 kilometres of highways are being constructed, rail networks expanded, new airports added, and inland waterways developed along the Brahmaputra and Barak rivers. Mobile telephony has spread deeper into remote areas, and a 1,600-kilometre-long Northeast Gas Grid (scheduled for completion by 2026, designed to harness the region’s abundant natural gas reserves) is being laid to integrate the region’s energy infrastructure with the rest of the country. In fact, this is expected to strengthen India’s energy security by allowing producers to market surplus gas both domestically and abroad, while also attracting new industries, creating jobs, and supplying affordable energy to sectors like tea estates.

Indian Railways alone reports that more than 1,679 kilometres of track have been laid since 2014, over 2,500 route kilometres electrified, and 60 stations taken up for redevelopment under the Amrit Bharat Station Scheme. The Bairabi–Sairang line was commissioned in June 2025, finally linking Aizawl to the national rail network. This makes it the fourth northeastern capital to be connected, nearly seventy-eight years after Independence. On paper, the region can no longer be considered peripheral.

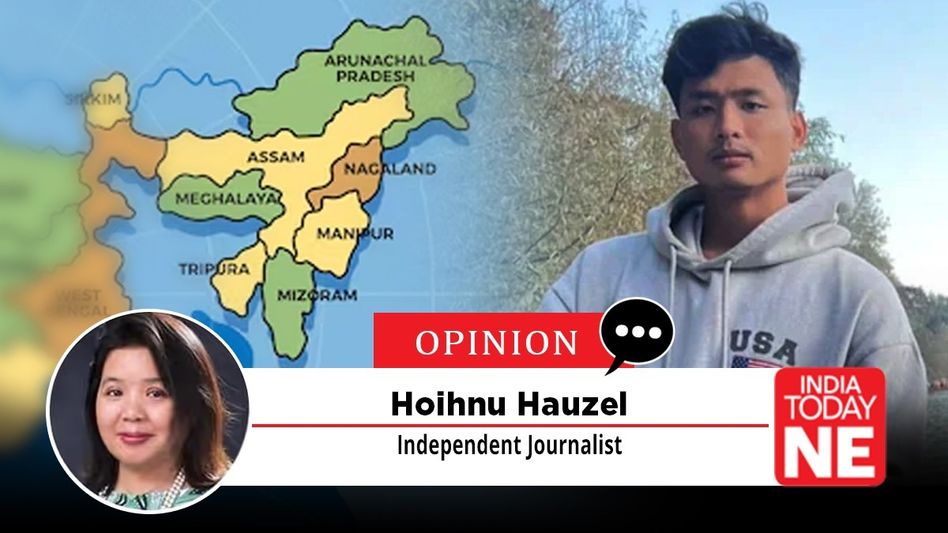

Yet geography continues to shape perception. The Northeast remains connected to the rest of India by a narrow strip of land in West Bengal, popularly known as the “Chicken’s Neck.” This thin corridor has long symbolised not just logistical vulnerability but a deeper sense of separation. Being linked by a sliver has often meant being treated as distant—strategically important, perhaps, but socially peripheral. Physical marginality has too often translated into emotional and political distance. It is in this context that a group of young, promising political leaders have begun joining hands to form a unified regional platform, called One Northeast (ONE), believing that the time is ripe to address the region’s concerns collectively and assert a stronger, coordinated voice in national affairs.

Cultural visibility has also surged. A young singing prodigy from Mizoram being invited to perform by India’s wealthiest family is a telling sign of how Northeast talent is entering elite national spaces. Popular OTT shows such as The Family Man, Paatal Lok and Delhi Crime have brought the region’s landscapes and border towns into mainstream storytelling. According to ixigo’s Great Indian Travel Index 2025, flight bookings to cities like Imphal, Dimapur, Agartala and Guwahati have risen sharply, placing the Northeast firmly on the travel map.

And yet, the persistence of racial violence raises uncomfortable questions. In 2014, after the death of Nido Tania, a 19-year-old student from Arunachal Pradesh who was assaulted in Delhi, the Ministry of Home Affairs set up a committee under the chairmanship of MP Bezbaruah to examine the racism and discrimination faced by people from the Northeast in Indian cities. The committee’s report, submitted the same year, acknowledged that these were not aberrations but systemic failures requiring sustained corrective action.

Nearly a decade later, the death of Anjel Chakma, a 24-year-old MBA student from Tripura, in Dehradun suggests that the underlying attitudes have not shifted enough. Reports that he had to assert his Indian identity before dying point to a contradiction that infrastructure alone cannot resolve. If highways, tunnels, railways and airports are meant to integrate the region, why does everyday prejudice continue to surface with such regularity?

This forces a harder question: does racial violence against people from the Northeast reflect an attitude that undervalues what is unfamiliar or not considered “mainstream”? At the core of every policy, infrastructure plan, and governance framework are people, yet development is often framed largely in terms of investment potential and tourism appeal. Social inclusion cannot be reduced to market logic. When regions are embraced primarily for their strategic value, scenic beauty or economic promise, their people risk being pushed to the margins of the national self-image.

Public attitudes often mirror institutional priorities. Would it be correct to assume that what the rest of India reflects in its behaviour toward people from the Northeast is, in many ways, shaped by how consistently and seriously the Centre has engaged with the region beyond infrastructure? Roads and railways can bridge distances, but they do not automatically dismantle prejudice.

This is the paradox of the present moment. The Northeast is being connected, counted and consumed—through kilometres built, bookings logged, and stories streamed—yet many of its people still carry the burden of having to explain who they are. The current spotlight could mark a turning point if it leads to deeper understanding and accountability. Or it could remain superficial, where visibility increases but belonging does not.

The overwhelming nature of this moment lies precisely here: a region more connected than ever before, still linked by a thin strip of land, and still asking why, despite all this progress, its people continue to be made to feel like outsiders in their own country.

Why, in the first place, should India have lost Anjel Chakma for who he was?

Copyright©2026 Living Media India Limited. For reprint rights: Syndications Today