India’s narrowest lifeline can no longer be treated as an afterthought

What sounded like a provocative remark about widening the Siliguri Corridor is, in fact, a reminder that India’s strategic vulnerabilities have not disappeared—only grown more consequential. The real question is not whether borders should change, but whether the country is prepared for the day when geography, not politics, tests the resilience of the Indian state.

- Sarma's proposal on Siliguri Corridor sparks varied reactions.

- Siliguri Corridor is crucial for Northeast India's connectivity.

- China's growth and India's Act East Policy heighten corridor's importance.

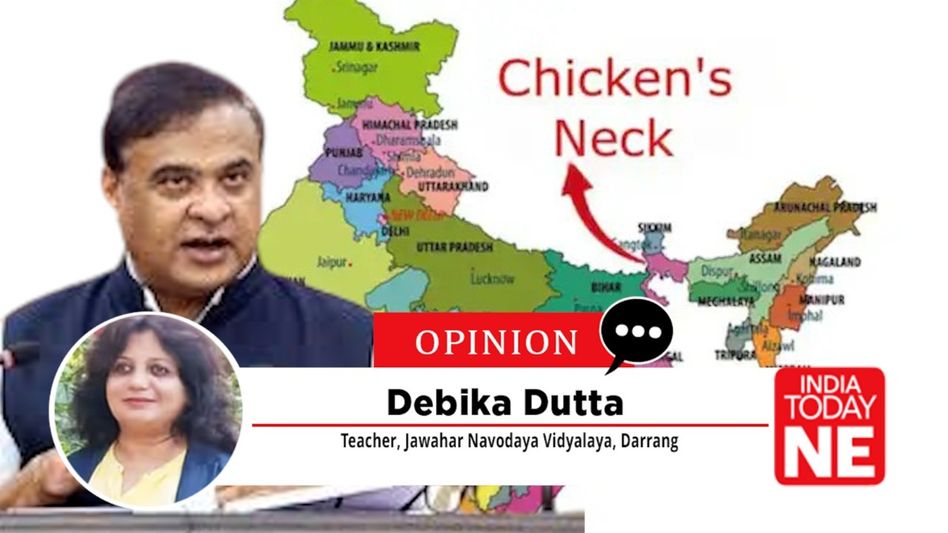

When Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma recently spoke of widening the Siliguri Corridor by roughly 22 kilometres, the response was swift and divided. Some read it as provocation, others as impractical speculation. Yet the remark, stripped of political reflex and rhetorical heat, raises a strategic question India has lived with for decades but rarely discussed openly: how resilient is the narrow land passage that connects the Northeast to the rest of the country, and how prepared is the Indian state to mitigate its inherent vulnerability?

The Siliguri Corridor—often called the Chicken’s Neck—is not a symbolic expression but a hard geographic fact. At its narrowest, it measures barely 20 to 25 kilometres. Through this constricted stretch pass national highways, railway lines, fuel pipelines, power transmission networks, and digital infrastructure that sustain eight Northeastern states and nearly 45 million people. Any prolonged disruption—whether caused by conflict, sabotage, natural disaster, or systemic failure—would have immediate economic and administrative consequences, effectively isolating the region. This vulnerability has long been recognised within defence and security establishments, even if it has remained largely outside public debate.

What has changed is not geography, but context. China’s rapid infrastructure expansion across the Tibetan plateau has enhanced its logistical reach and mobility along India’s northern frontier. South Asia, meanwhile, is experiencing political churn and sharper public narratives that occasionally spill across borders. At the same time, India has consciously repositioned the Northeast as a strategic and economic bridge to Southeast Asia under the Act East Policy. This shift—backed by heavy investment in roads, railways, airports, waterways, and border trade points—has increased both civilian and strategic traffic through the Siliguri Corridor, making its uninterrupted functioning more critical than ever.

Read in this light, Sarma’s remarks are best understood not as a policy demand but as a strategic prompt. Decisions relating to borders, security architecture, and international engagement rest firmly with the Union government, and there has been no indication of any departure from India’s long-standing commitment to diplomacy, regional cooperation, and international law. The chief minister’s intervention instead foregrounds the idea of strategic depth—an issue that responsible states routinely examine as part of long-term planning.

Much of the criticism has centred on the literal interpretation of “widening”, particularly the suggestion that it implies territorial expansion at the expense of a neighbouring

country. Such readings overlook both practical reality and stated policy. India’s neighbourhood-first approach, its strong bilateral engagement with Bangladesh, and its emphasis on connectivity through cooperation rather than coercion make any notion of unilateral territorial action implausible. Strategic vulnerability, however, can be acknowledged without prescribing dramatic or immediate remedies.

Assam’s particular concern is rooted in experience. As the logistical hub of the Northeast, the state would be among the first to feel the effects of any disruption at Siliguri. Fuel supplies, essential commodities, medical logistics, industrial inputs, and even digital services depend on the corridor’s stability. The economic shock of a prolonged interruption would be swift, with cascading effects across agriculture, industry, and daily life. Beyond economics lies a psychological reality: for a region that has historically grappled with a sense of distance from the national core, the fragility of its only land link reinforces old anxieties. Strengthening resilience, therefore, is as much about confidence as it is about security.

Opposition voices have cautioned that public discussion of such vulnerabilities could complicate India’s relations with its neighbours, particularly Bangladesh, with whom cooperation on transit, counter-terrorism, and trade has delivered tangible benefits. This concern deserves respect. Diplomatic engagement thrives on trust and stability, and India has consistently shown restraint in managing sensitive issues. Yet mature statecraft also involves internal clarity. Acknowledging structural challenges within policy circles and public discourse does not undermine diplomacy; it strengthens it by ensuring preparedness is grounded in realism rather than assumption.

Questions of feasibility have also been raised. Expanding physical space in a densely populated and environmentally sensitive region would involve complex political, financial, and administrative considerations. That is undeniable. But strategic planning is not an exercise in convenience. India’s experience—whether in border infrastructure or defence procurement—shows that delayed recognition of challenges often proves costlier than early, incremental preparation. The issue is not immediate execution, but long-term mitigation.

There is, too, the argument that advances in technology reduce dependence on land corridors. Airlift capability, digital connectivity, and diversified supply chains certainly enhance flexibility. Yet recent global conflicts and humanitarian crises underline a consistent lesson: physical connectivity remains central to resilience. Technology augments geography; it does not eliminate it. Strategic security is built on redundancy, not substitution.

The more constructive response to the current debate lies in expanding existing policy pathways. Reducing over-reliance on the Siliguri Corridor does not require dramatic cartographic solutions. It aligns naturally with steps already underway: deeper use of

transit agreements with Bangladesh, accelerated development of the India–Myanmar–Thailand Trilateral Highway, sustained investment in inland waterways along the Brahmaputra and Barak, and the creation of multimodal logistics hubs across the Northeast. Simultaneously, the corridor itself can be strengthened through better surveillance, disaster-resilient infrastructure, and coordinated civil-security planning—measures entirely consistent with current government initiatives.

At its core, the Siliguri question is not about altering borders, but about matching ambition with foresight. The government’s vision of the Northeast as an engine of growth and a gateway to Southeast Asia rests on assured connectivity. Development without security is fragile, while security without development is unsustainable. The two must move together.

Himanta Biswa Sarma’s remarks may have unsettled some, but they perform a useful function. They remind policymakers and citizens alike that geography imposes constraints even as policy creates opportunity. The narrowness of the passage is a fact. Whether it remains a strategic liability is a matter of planning, coordination, and political will. Addressing that challenge calmly, within constitutional and diplomatic frameworks, is not a departure from policy—it is its logical continuation.

Copyright©2025 Living Media India Limited. For reprint rights: Syndications Today