Roi Roi Binale review: Zubeen Garg's ode to life, his last and loudest, goodbye

There are films that leave an impression. Then there are those that become elegies not merely stories told through the screen but living testaments to an artist’s life and its echoing afterglow. Rajesh Bhuyan’s Roi Roi Binale belongs unmistakably to the latter category.

- Nov 06, 2025,

- Updated Nov 06, 2025, 3:26 PM IST

There are films that leave an impression. Then there are those that become elegies not merely stories told through the screen but living testaments to an artist’s life and its echoing afterglow. Rajesh Bhuyan’s Roi Roi Binale belongs unmistakably to the latter category. Written by and starring the late Zubeen Garg, the polymathic icon of Assamese music, cinema, and conscience the film transcends its genre to become a collective farewell. Released barely a month after Garg’s untimely passing in a swimming accident in Singapore, it now feels less like a film premiere and more like a memorial, a mass catharsis disguised as a love story.

For thirty years, Zubeen Garg’s voice defined an emotional vocabulary for Assam from insurgency-scarred alleys to joyous festive nights, his melodies carried both lament and light. By the time of his death, he had sung over 38,000 songs in forty languages, directed films, penned lyrics, composed symphonies, and embodied the impossible alchemy of art and rebellion. In Roi Roi Binale, his final performance, Garg plays Rahul (Raul) a blind singer whose vision of life, as the script reminds us, is sharper than that of the sighted. In fiction, he loses sight. In truth, he sees everything.

The parallel is no accident. Garg’s Rahul is a mirror, shimmering with the real artist’s resolve, humor, frailty, and faith. The film opens with Rahul arriving in Guwahati, “the city of dreams,” where he must carve his place against a world that sees his disability before his music. Yet what unfolds isn’t a story of disadvantage or pity; it’s a portrait of inner freedom. As Rahul sings his way into the hearts of strangers Debu (Saurabh Hazarik), the empathetic restaurant owner; Mou (Mousumi Alifa), the ambitious yet tender-hearted manager; Neer (Joy Kashyap), the established singer searching for meaning we realize that Roi Roi Binale isn’t about blindness at all. It’s about clarity.

It would be sacrilege to speak of a Zubeen Garg film without dwelling on its music. The soundtrack of Roi Roi Binale is a cathedral of emotions, an aural diary written in his own voice. Every composition feels devotional not in faith, but in creative surrender. The titular track, “Roi Roi Binale,” reimagines a haunting 1998 melody from Garg’s early years, transforming it into an anthem soaked in both nostalgia and farewell. Each sequence carries musical texture that elevates the film beyond dialogue. The strings bleed, the percussion swells, and Garg’s voice reconstructed partially through AI after his death glides through both reality and remembrance with uncanny intimacy.

Poran Borkatoky, Garg’s protégé, completes the unfinished score. The result is seamless: an invisible thread tying master and disciple in posthumous collaboration. It’s as if Garg himself had whispered instructions from the ether leaving behind fragments of rhythms he never finished, now completed by those who owed their art to him.

Bhuyan’s direction is old-fashioned in the best sense unhurried, sentimental, even indulgent. The film thrives on simplicity, unashamedly leaning into melodrama. Yet, beneath the conventional structure lies subtle political subtext. The Assam of Roi Roi Binale is a land of wounds healing under song. The echoes of militancy, the quiet unease of cultural displacement, the resilience of ordinary people they pulse gently underneath the romantic veneer. When Rahul tells Mou that “music cannot change the world, but it can stop it from becoming worse,” it’s as though Garg himself were speaking to a generation trying to reconcile beauty with pain.

Midway through, the film shifts tone from hopeful crescendo to existential murmur. The relationships begin to strain under ambition, love fractures under ego, and the film risks meandering into sentimentality. Yet, the emotional payoff lies not in dramatic twists but in lived texture. Garg’s restrained performance anchors the narrative. His pauses, his quiet smiles, his offhand wit they are human, not heroic. He doesn’t act; he feels.

After Garg’s passing, the production team faced immense challenges incomplete dubbing, missing background scores, and, most dauntingly, the absence of the artist himself. What followed was an act of devotion, not production. Engineers, musicians, and AI specialists painstakingly restored fragments of his voice, sometimes from set audio, sometimes from archival interviews. The goal wasn’t perfection; it was preservation. When Rahul sings his final song onscreen, the audience knows intuitively that both the character and zubeen is bidding farewell, his final goodbye to the people of Assam.

At some point during that song, the theater goes silent, except for muffled sobs. The boundary between filmgoer and participant dissolves. You are not watching Roi Roi Binale. You are living it, mourning through it, and remembering with it.

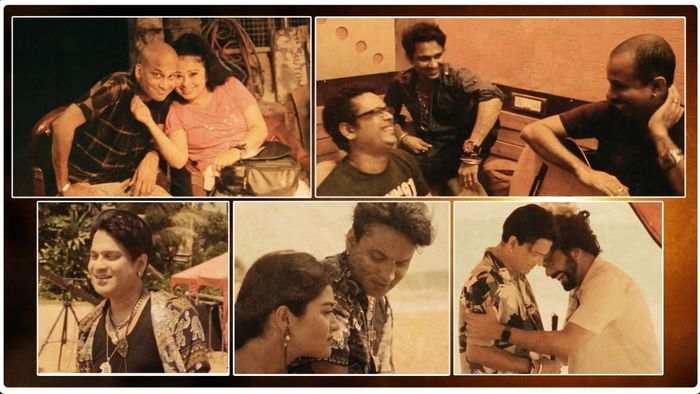

What truly lingers, long after the final credits, is the closing montage, a homage reel underscored by the reprised title track. It’s an emotional gut-punch: images of Garg in concert, laughing with fans, walking barefoot into a river, interlaced with the faces of the film’s cast watching him vanish into sunset light. The moment captures what Assamese cinema has always been at its best: emotionally transparent, community-driven, and deeply individualistic.

If Garg was the troubadour of the Brahmaputra, then Roi Roi Binale is his final boat song, a drifting, shimmering elegy to a man who turned art into resistance and songs into scripture.

Narratively, Roi Roi Binale is imperfect. Its second half lags, its editing indulges, its dialogues sometimes repeat themselves. Yet, it’s precisely this vulnerability that makes it human. Cinema, like song, doesn’t seek flawlessness; it seeks truth. And truth is what Garg offers — about music, identity, and mortality. The blind musician’s search for self mirrors the artist’s own unfinished search for meaning.

With its modest cinematography, restrained performances, and emotionally raw heart, Roi Roi Binale elevates itself beyond the label of a film into something more sacred, an experience. Zubeen Garg’s swansong is the kind of farewell few artists are privileged to make: one that vibrates across time, reminding us that legends don’t die; they modulate.

In Assam, screenings began at dawn. Theatres reopened after decades. Fans lit candles, offered prayers, held concerts outside cinema halls. It wasn’t mourning in the traditional sense, it was communion. A people remembering their voice by hearing it one more time. “Roi Roi Binale,” roughly translating to tears upon tears, became not just a title, but an invocation. What Assam wept for was not only an artist lost, but an era ending one where melody still mattered, where songs still spoke of soil and soul.

In the end, Roi Roi Binale doesn’t just close a chapter in Assamese cinema. It turns Zubeen Garg’s own life into an unending chorus. For every listener, it whispers the same quiet truth he once lived by: that love, when sung with sincerity, never truly fades.