Why Assam's Kamakhya Narayan Singh chose to make The Kerala Story 2

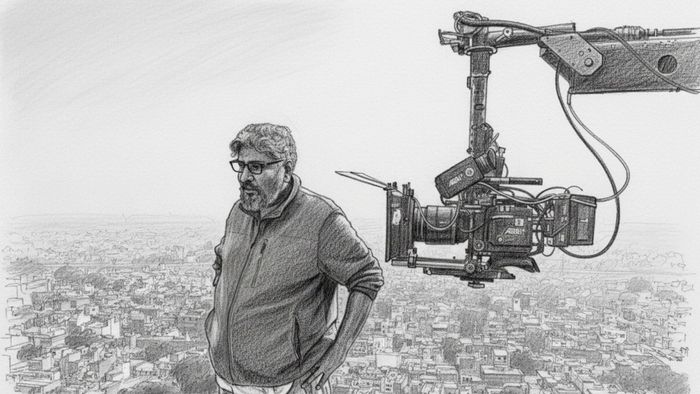

National Award-winning filmmaker Kamakhya Narayan Singh has never shied away from difficult subjects—but with The Kerala Story 2: Goes Beyond, he steps into his most defining chapter yet. As the film releases, the question is not just how the country will respond, but whether this bold turn will reshape the legacy of a director who believes cinema must create impact.

- Feb 22, 2026,

- Updated Feb 22, 2026, 3:15 PM IST

Kamakhya Narayan Singh grew up in Ganeshguri, Guwahati, during the 1990s, when the ULFA insurgency was at its height. It was a turbulent time in Assam's history, but one that shaped his worldview.

"I am from Guwahati," Kamakhya says when asked if he's worried about threats ahead of his film's release. "Do you think a Guwahati boy will be scared of these people?"

Now 41, the National Award-winning director is at the centre of one of 2026's biggest controversies. His film The Kerala Story 2: Goes Beyond releases on February 27, and it's already generating heated debate. But Kamakhya isn't 'most' filmmakers.

Just six years ago, Kamakhya was being celebrated on the international festival circuit for Bhor, his sensitive portrayal of a young Musahar girl in Bihar fighting for education and dignity. The film travelled to 28 international festivals, won best director awards in Ottawa and Boston, and showcased Kamakhya's commitment to telling stories about India's most marginalised communities.

He cast complete unknowns from the actual Musahar community. They lived in villages for two months to prepare. The costumes weren't rented from Mumbai designers but borrowed from actual villagers, who received new clothes in exchange. It was documentary-level realism applied to narrative filmmaking.

"As a filmmaker and a student of social work, I had the chance to travel the world and India extensively," Kamakhya explained at the time. "I got a chance to interact with people from indigenous cultures. They may be poor, but they are happy. There are conflicts, but they are not complicated."

That sensitivity earned him India's highest cinematic honour. In 2022, he won the National Film Award for Best Film on Social Issues for his documentary Justice Delayed but Delivered. In 2025, he won another National Award for Timeless Tamil Nadu, a travel documentary about culture and heritage.

So how did this thoughtful documentarian end up directing the 'spiritual' sequel to one of the most divisive films in recent Indian cinema?

Kamakhya says it wasn't a sudden shift. For three to four years, he's been researching demography, studying how population patterns change and what drives those changes. When producer Vipul Amrutlal Shah announced plans for The Kerala Story 2, Kamakhya's friend and the film's writer, Amarnath Jha, suggested they talk.

"I was working on demography," Kamakhya explains. "So this was part of it. I read the case files. And a lot of victims, a lot of parents who have been suffering from this conspiracy and how their daughters have been subjected to something which is not needed."

The trigger came closer to home than research papers. In his Mumbai neighbourhood, Kamakhya met two women whose stories shook him. One was a divorcee who had fallen in love, gotten married, and found herself pregnant. "She was forced to abort the child," Kamakhya recounts. "'If you don't convert, you will not be able to get pregnant,' she was told."

The second case involved economic pressure. "She was forcefully made to eat beef if she wanted to stay with that man because she came from a poor section of society. She could not go back as she was married in an interfaith marriage."

These weren't abstract statistics. These were his neighbours.

The Kerala Story 2 tells the stories of three young Hindu women from different parts of India. Surekha (played by Ulka Gupta) is from Kerala. Neha (Aishwarya Ojha) is from Madhya Pradesh. Divya (Aditi Bhatia) is from Rajasthan. All three fall in love with Muslim men. All three find their lives spiralling into tragedy.

"We wanted to tell people that it has spread across India," Kamakhya says. "It's not a story of one street, one neighbourhood, one state. It's a story of the country. There are people who are conspiring to change the demography of this country, and they are using love to use our daughters to change the demography."

The research process was extensive. Kamakhya says he read nearly 1,500 articles over six to seven months. He studied 70 FIRs from across India. He points to specific cases like Jamaluddin alias Chhangur alias Jhangur Baba in Uttar Pradesh, where police claim a syndicate targeted at least 1,000 girls.

"When you connect with the idea of Ghazwa-e-Hind, when they claim, 'yes, we want to turn this country into Ghazwa-e-Hind', and then you see these modules, you feel no girl in this country is safe," he says. "And trust me, there is no false data used to make this film."

Growing up in Assam gave Kamakhya a unique perspective on identity politics and demographic change. His very name carries that weight—Kamakhya, after the ancient goddess worshipped at Guwahati's Kamakhya Temple, one of the 51 Shakti Peethas, a symbol of feminine power and creative energy. It's an unusual name for a filmmaker, but perhaps fitting for someone drawn to stories about women in crisis.

The state has struggled for decades with questions of who belongs and who doesn't, from the language movements of the 1960s to the NRC controversy of recent years.

"It made me a more sensitive artist," Kamakhya says of his Assamese upbringing. "Assam brought culture and tradition closer to all these things."

But he also acknowledges a darker influence. "The way the demography of Assam is changing, it makes me more and more conscious to make such films."

His concern echoes what has become a defining issue in Assam's politics. Just last October, Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma claimed that Assam's Muslim population has reached nearly 40 per cent, roughly equal to the Assamese Hindu population. "Assam has long been a victim of demographic change due to decades of illegal infiltration," Sarma said, calling it a reality that now defines the state.

In February 2026, Sarma went further, claiming the Assamese community will become "almost a minority" in the 2027 census. It's this narrative—of a community feeling its identity threatened by demographic shifts—that seems to inform Kamakhya's filmmaking choices.

Assam's demographic shifts have been a source of tension since Partition. The state absorbed waves of migration from East Pakistan and later Bangladesh. Indigenous Assamese communities have often felt their identity threatened. The 1983 Nellie massacre, where nearly 2,000 Bengali Muslims were killed, remains one of independent India's worst communal atrocities.

WATCH THE TRAILER:

Does that history inform The Kerala Story 2? Kamakhya doesn't directly answer, but his passion about the subject suggests deep personal conviction. "I don't know what controversy is," he insists. "See, as a filmmaker, I'm a sensitive filmmaker. I would always make films which have emotions, which have to do with society. Bhor was also the same. Justice Delayed But Delivered was also the same. I have always made rights-based films. So, I have always worked on civil rights. I feel somewhere in this area of my work, the demography, how the girls have been used in love jihad, this is also part of our civil rights."

Kerala's government has already condemned the film. Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan called it "communal propaganda" and "poisonous work." Critics are using terms like "Islamophobic" and "hate film" before the movie has even released.

Kamakhya's response is direct. "Every day, there is a case in the news of this kind. I would humbly request that the Kerala Chief Minister meet the victims. In Kerala Story 1, we had shown the victims of love jihad in Kerala. Did he, in the last three years, get time to meet them? No. So, he has no right to tell us that we are doing propaganda. Let him go. Let his representative go and meet them."

When pressed about whether all the Muslim characters in his film are villains while all the Hindu characters are victims, Kamakhya makes a comparison that reveals his thinking. "In Sholay, Gabbar Singh was the villain. Did anyone say that because Gabbar Singh was a Rajput, we portrayed Rajputs as villains? No. Whatever facts we found, we presented them as they were; we cannot divide everything along religious lines. In this story, the boys were the villains, and they were Muslims, so I had to tell the story that way."

Kamakhya is adamant about his intentions. "If anyone who is non-violent and who is not part of this kind of conspiracy is harassed, it's a wrong thing. It should not happen. But it doesn't mean that I do not bring out the truth."

Unlike the first Kerala Story, which focused on victimhood, Kamakhya's sequel emphasises resistance. The tagline is "Ab sahenge nahin, ladenge"—We won't tolerate anymore, we will fight.

"The fight is against those people who are doing the conspiracy," Kamakhya explains. "We want our daughters to be strong. Sometimes, when you suffer, there are different ways of narrating the story. Once you are trapped in this kind of situation, you cannot come back. We want to tell parents and society that we must accept our daughters. In that way, we want to fight back."

ALSO READ: From Assam to Tribeca Festival: Rajdeep Choudhury’s “A Teacher’s Gift” makes its mark

The film opens with a stark warning that India could become an Islamic state in 25 years. Where did that claim come from? "There is a PFI document which the NIA has submitted," Kamakhya says. "As a researcher, you have to connect the dots. The first document says they will turn this country into Ghazwa-e-Hind. The second document shows that girls are trapped in the web of love, married off, converted, forced to follow fundamental rules, and confined inside their homes. Is this the kind of society I would want? That is the question."

The filmmaker frames his work not as entertainment but as a social mission. "I am feeling more responsible because this film is not about entertainment, it's about bringing out facts to society, telling them we need to be aware of it," he says. "So I feel more responsible. I am nervous—not because of what I have done, but because it is a huge responsibility on my shoulders to carry such messages."

He believes that raising awareness about what he sees as a real issue is his responsibility as a filmmaker, regardless of criticism.

Kamakhya's path to filmmaking wasn't overnight. He started in television, producing shows like Quest and Music Ka Tadka, before moving to documentaries. His documentary work earned him not one but two National Film Awards—one for Justice Delayed but Delivered in 2022, and another for Timeless Tamil Nadu in 2025.

Now, directing a big-budget Bollywood sequel is a milestone. "It's a journey, I would say," Kamakhya reflects. "It takes time. You should be hopeful. You should keep working. I see my journey in life as work. The work will keep coming."

The casting for The Kerala Story 2 also marks a shift from his earlier approach. For Bhor, Kamakhya wanted complete authenticity. "I really wanted to work with people with no acting background. But then I realised it would be very tough. So I chose theatre actors to do it." Mainstream actors had refused the unglamorous project.

For The Kerala Story 2, he's working with recognisable television faces—Ulka Gupta, Aditi Bhatia, Aishwarya Ojha—who bring audience connect and star power. The film will be released first in theatres, then perhaps move to OTT platforms. "Mass has to watch this film," Kamakhya says.

Some will say Kamakhya has traded artistic integrity for commercial success. His response is straightforward. "They can say whatever they want. As a filmmaker, you have to ask questions. If I am seeing 1,500 news reports, if news channels are reporting on this every single day, if there are court decrees addressing issues of so-called 'love jihad', and our daughters are dying—would I want that? Would I want our daughters and sisters to be killed or forcefully made to wear a burqa after being lured into love? Since I would not want that to happen, I will address the issue as a filmmaker, as an artist, through my art, through film."

He sees himself as someone pointing out what others prefer to ignore. "When society thinks it is happening in some small places, I need to tell them: No, it's not happening at only one place or in one city or one neighbourhood. It's happening in Bhopal also. It's happening in Jodhpur also. It's happening in Agra also. It's happening in every state."

Kamakhya says his future will include both kinds of films—commercial projects like The Kerala Story 2 and intimate stories like Bhor. He promises that soon he'll make a big film about Assam or the Northeast. It's a promise Northeast audiences have heard before from filmmakers who find success in mainstream Bollywood, but Kamakhya, who still carries Guwahati in his voice and conviction, might just keep it.

When asked what he wants to be remembered for twenty years from now, his answer surprises. "Good films, very good films, which can help society in some way. Impact—if I can create impact with my films."

Then he pauses and adds something more personal. "But I would not want to be remembered. I do a lot of travel documentaries. I've travelled to more than 50 countries, but I don't have a souvenir from any country. I don't want anything to be permanent. You should contribute through your work, which has to create an impact in society. Whether your name is there or not, let history decide. Nobody's going to remember anyone after a few years, but your work has to be remembered."

It's a humble statement from a man making anything but a humble film. Whether The Kerala Story 2 will be remembered for the right reasons or the wrong ones remains to be seen.

But one thing is certain: Kamakhya Narayan Singh, the sensitive documentarian who made Bhor and won National Awards, has made a choice. He has decided that some stories need to be told loudly, controversially, and without apology.

The filmmaker from Guwahati has placed his bet. Now we all wait to see what happens next.

ALSO READ: The One That Got Away