Dehing Patkai and roots of indigeneity: 4. The Tai Khamyang

Dehing Patkai and roots of indigeneity: 4. The Tai Khamyang

Dehing Patkai and roots of indigeneity: 4. The Tai KhamyangIn the last few months a major movement has been created over the social media that aims at drawing public attention towards the destruction of the Dehing Patkai rainforest. This destruction is primarily attributed to the coal mafia that has been conducting illegal open cast mining in the forest. Although voices have always been raised against this system, it reached its peak with the government decision to grant mining permissions to Coal India Limited in Saleki Proposed Reserve Forest which falls under the contiguous belt of Dehing Patkai Rainforest.

The movement seeks to protect the forest by raising mass awareness about the many species of flora and fauna that call it their home and face a threat of habitat loss if the mining is allowed to continue. That these species include the state bird of Assam, the white winged wood duck and the state tree of Assam, the Hollong tree only increased the public sentiment. The Chief Minister of Assam recently announced that the forest will be declared a national park, thereby increasing the level of protection for the forest. He also ordered an investigation into the allegations of discrepancies in the forest under retired judge B P Katakey. The DFO of Digboi Forest Division, Atiqur Rahman was transferred due to his involvement in the deforestation and timber smuggling rackets.

There is another impact of these activities as well which has not been highlighted as much. For centuries, the forest and its adjoining areas have been the homes of many indigenous communities of Assam. These people have lived and grown with the forest and the Dehing river and have traditions as well as day to day activities that consider the forest as well as the river a part of their own. Through three previous articles, we have talked about the way that the depletion of the forest and pollution of the river affects the Tai Phake, Singpho and Nocte communities. This last and final piece brings forward the story of another such age old tribe.

The Tai Khamyang

The Khamyangs are one of the many sub groups of the Tai ethnic group and one of the six that made their way to Arunachal Pradesh and Assam from the South East Asian valleys. In Assam they are also known as the Shyam people, a name that is often said to have its origin in the word Siam which was used to refer to Thailand. Since recorded memory the Khamyangs follow Buddhism and the monastery or vihar plays a central role in the village. The word Khamyang is a Tai word combining two words; Kham meaning Gold and Yang meaning to have. This has its roots in their home in Kachin valley of Myanmar and the practice of collecting Gold from the rivers. The Khamyangs in Assam have close relations with other Tai groups like the Tai Phake and the Tai Khamti and are now spread over the districts of Tinsukia, Dibrugarh, Sibsagar and Jorhat.

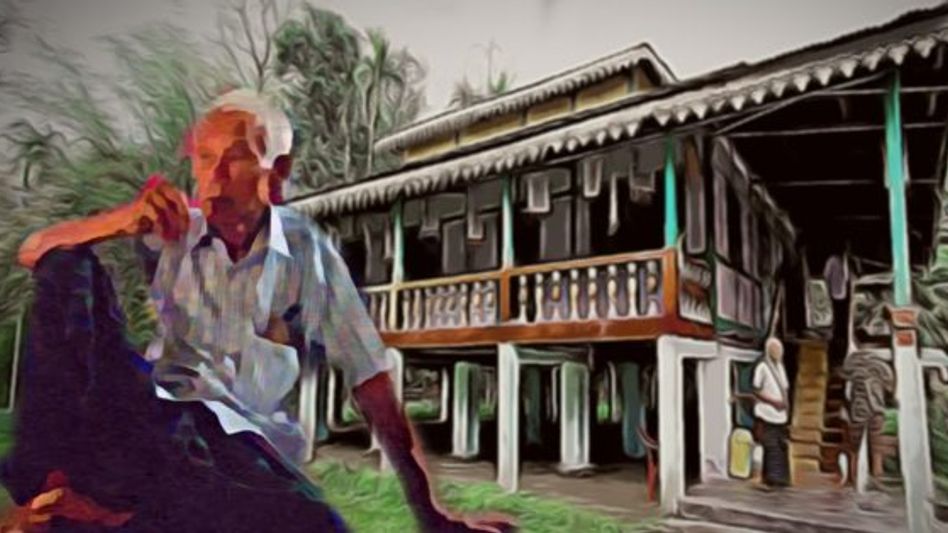

The Village Elder

We went to the Pawoimukh Khamyang Village near Margherita. This village housing around fifty families is home to the last speakers of the Khamyang language. We first approached the monastery as we did in Namphake. The chief priest or the Bhante was but a young monk of eighteen. He was kind enough to arrange for us to meet a village elder. A little while later, we sat in front of Mr. Bhogeswar Thumung and heard him speak in fluent Khamyang to one of his friends. Then he turned to us and spoke to us in fluent Assamese.

We asked him whether he remembers the settlement of the village. “We came from Khamti Ghat in Dibrugarh. It was a village with Khamti majority and both our tribes co-existed. In 1942, during the time of the war, the Britishers moved us to another location inside the forest because this area came under the shelling zone of the Japanese forces. That village was called Lakhimi. The conditions were not very favorable and many of the old men fell ill and perished. Later when the conditions normalized, we came back and this village was reestablished. We were kids back then.”

The Khamyang language in itself has gradually lost its speakers and the last of the speakers were limited to the village elders of Pawoimukh. We asked Thumung about his opinions regarding this and the elder replied, “The end of the Khamyang language is very near. The reason is its diminished usage. As the years passed, the concept of holding on to the mother tongue was lost. We are a very few who can read, write or speak the language. But this is not the case with the younger generations. One of the big reasons, I believe, is the inter community marriages. For example, suppose a Khamyang boy married a wife from some other community. Later the man dies. There remains no one in the household to ensure the use of the language among the next generation. The way things are, it will go extinct for sure. No one can stop that from happening. I’ll guarantee thirty more years maybe, not more than that.”

The pain one must have felt to admit that his mother tongue will cease to exist in a matter of three decades is hard to imagine. Upon being asked whether he sees any way out of this, the senior told us, “There might be a way to preserve it if the Government or some NGO tries to do it by recording it after conducting substantial research on the topic. We have had such instances before. Stephen Murray from Australia stayed here for eighteen years documenting the many languages and cultures. But I don’t think it will ensure the revival of the language. That will only be possible if the practice and usage of the language increases. The younger generations got educated and had to move out in search of employment. They were introduced to a different society where the practice died.”

“Maybe it is because your numbers are less and there are few people to practice the language with?” we ask. To this Thumung smiled and said, “Even with few people it is possible to hold on to the language if you can instill its pride among the younger generations. Few of the young ones were influenced by the foreign exposure and are even ashamed to speak their own mother tongue. So to revive the language, we have to have institutionalized training now to encourage the children to learn their own language.”

“What about this monastery?” we ask. “Can’t this act as a center of learning?” “It did once upon a time.” Bhogeswar Thumung tells us. “But as I said, once the children are sent out for higher education, they will always venture out for employment opportunities. Why would then they return to the monastery to learn things?”

About environmental changes

“There has been a lot of pollution over the years.” Thumung tells us when we ask him about the environmental changes that he has witnessed through his lifetime. “Previously we used to drink the river water itself. Till our young years we could do that. Now it is not possible. Even fishes were in plenty and we used to get big catches very easily. But now all the fertilizers and pesticides from the tea gardens have killed a big population.”

Upon being asked about the impact of illegal coal mining in the hills, he said, “Due to coal mining the rivers are awash with pollutant wastes along with the gases that evolve during the mining process, there’s no question about it. We also see clumps of coal being carried downstream by the river. This has particularly increased since around the late 70s or early 80s. Previously they were a little covert about it but now they have been openly using dumpers and JCB excavators to destroy the hills entirely.”

It is to be noted that many mention the initial years of the coal mafia syndicate and illegal coal mining operations to be around the same period when a section of surrendered militants were said to take up the illegal mining of coal.

Dependence on the forest

“We used to depend on the forest a lot for household needs like bamboo, cane, wild fruits and vegetables. Traditional vegetables like Kuji Thekera, Kawoi Tenga were in abundance; all of that has disappeared now. Timber extraction by traders in Naharkatiya is the main reason behind that. Most of them were traders in Jeypore who have reduced these activities now. There is one person called Yakub from Naharkatiya who still maintains it though. He is in good relations with ministers as well. He transports the timber by way of the river downstream.”

We asked if people from the village were involved in this as well. “Earlier the people used to take part in the timber extraction. This was primarily due to lack of employment. With the use of modern technology like chainsaws, it only serves as a means for easy money. Our children have come to realize the impacts now and do not participate in it anymore. They understand that it would cause damage to their own society and community.” In the end he adds with a smile, “The poor are the ones who need a society, isn’t it? The rich can build their own society where ever they wish to. It’s the poor who are stuck with building their old societies.”

The way forward

Listening to Bhogeswar Thumung, it was clear to us that creating employment opportunities for the educated youth of the region would go a long way in preserving their language and traditions. This is in fact very much possible from the perspective of Dehing Patkai rainforest. The forest can act as a great option for sustainable eco-tourism and niche tourism projects like Butterfly tours, wild life photography, jungle trekking and camping, river safari on the Dehing, food tourism aimed at showcasing the diverse cuisine of the many tribes and communities of the region etc. These options can be successfully promoted by national tourism strategies considering that they are a more sustainable way of developing tourism with relatively lower tourists but ones with genuine interest in the destination.

Apart from this there are also prospects in silk worm farming. The villages in the borders of the forest participate in farming silk worms. But even here the environmental standards have to be optimum since higher temperatures are not conducive with rearing silk worms. As mentioned by Nava Kachari, a local sericulture expert, the increased temperature due to depletion of the forest cover has created tough situations for the trade as the worms do not survive in high temperatures.

Increased employment opportunities will cause lesser number of people to venture out in search of petty jobs thus ensuring better connection with their indigenous roots. At the same time it will motivate the later generations to stay away from illegal activities of coal and timber mafia syndicate, thus taking a step forward in preserving the last of the lowland rainforests of India.

Readers like you make Inside Northeast’s work possible

To support our brand of fearless and investigative journalism, support us HERE.

Download:

The Inside Northeast app HERE for News, Views, and Reviews from Northeast India.

Do keep following us for news on-the-go. We deliver the Northeast.

Copyright©2025 Living Media India Limited. For reprint rights: Syndications Today