Dehing Patkai and roots of indigeneity: The Singphos

Assam Congress objects to draft EIA, writes to Environment Ministry

Assam Congress objects to draft EIA, writes to Environment MinistryThe Dehing Patkai rainforest has been in news and social media since the last few months because of the coal mining, legal or illegal, in and around the forest. The decision by NBWL to grant mining lease clearance to Coal India Limited in a Proposed Reserve Forest area called Saleki, under the same contiguous forest pushed it into national limelight. A movement against the government decision and with the general mission to protect the rainforest achieved popularity over social media. The movement that began with students and nature activists soon gained members from across the population spectrum. Recently, according to Government instructions all coal mining operations were suspended in the area and the Chief Minister also announced the decision to upgrade the status of the wildlife sanctuary to a National Park.

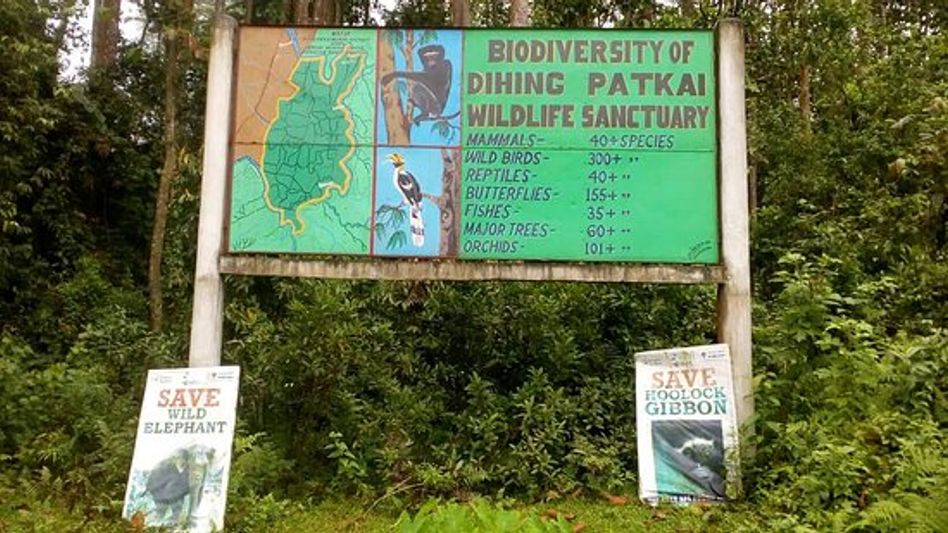

A lot of discussion has been concentrated on the grave threat posed by the destruction of the forest cover on the flora and fauna of the forest. The fact that the forest is a home to many endemic and endangered species including the state bird and state tree of Assam, makes the risk to the non-human species even more significant. But along with the plants and animals, the region is also home to some of the oldest indigenous tribes of Assam. These tribes have been historically dependent on the forest and the Dehing river, upon which the entire Dehingporiya civilization thrives. Encroachment and depletion of the forest has a direct influence on the way that these communities have interacted with nature for the many years of their settlement. In a previous article, we talked about the Tai Phakes and we move on to another tribe in this report.

The Singphos

The Singphos are an ethnic group that trace their origin to the Kachin state of Myanmar. Their presence is found across the three countries of Myanmar, China and India. In Assam, they are primarily settled in the Tinsukia district. The region was once referred to as Ojanti muluk (Unknown Territory). Later it fell under the North East Frontier Agency (NEFA). Under Gopinath Bordoloi’s regime the region was classified under the Tirap Transfer Area which was a restricted tribal belt. Singphos are one of many Tibeto-Burman tribes that are part of the indigenous tribes of Assam. They are particularly known for being the ones to introduce the British explorers Robert Bruce and his brother Charles Alexander Bruce to tea which later led to extensive tea cultivation in the state. The primary occupation of the tribe is agriculture. The Singphos still have their unique culture intact with their own dialect, cuisine, dress and architectural style.

The King

We drove to the north east of Ledo town through the Ledo tea estate to the Bissa village. The village located on the banks of the Tirap river is home to a majority Singpho people along with their titular king, Bissa Raja. We met the cheerful king and wished to gather his views and opinion as to how the community that has lived through so many changes and developments and the effect of the coal mining and other resource exploitation in the region. His answers were a mixture of divine philosophy as well as dialogues of experience.

“People’s ego has risen over the years. We are already at the dusk of our lives. Let us see where the next generation goes. We all have to return to the same place, our ancestors used to say.”

Significance of Dehing Patkai

We asked the Raja about the dependence of the tribe on the river and hills that forms the Dehing Patkai forest. He mentioned the divine significance of the natural features on the tribe. “We have always worshipped nature; the river god and the mountain god. They have now broken and destroyed large parts of the mountains for personal gains. This is not at all sustainable. If they do injustice to the mountain god, the one we call Mahadeo or Dangoriya, there will surely be divine retaliation in some way.” Sustainability of this venture is indeed a question for the future. The coal that is being mined from the forest for many decades now will possibly last for a century or a half of it. But the forest that is being destroyed to create these mines have formed an ecosystem over the course of many thousand years and any amount of compensative afforestation will not result in the same ecosystem to be reestablished.

Also read: The Tai Phake: Dehing Patkai and roots of indigeneity

“The sins of the father are repaid by the sons. We all know that the deity resides in the mountain. But they are breaking it down for coal even after this knowledge. This will surely bring some kind of a judgment day. This is how Assam is suffering due to people’s greed now.”

On illegal coal mining operations

As an octogenarian who had been living in the region for his entire life, Bissa Raja has seen the changes that were brought about after the mining operations intensified. As he showed us around his house built in the traditional Singpho architectural style, we asked him to let us know about this change from his own experiences. “When we were kids, we used to steal pins from our father’s desk and use them as fishing hooks in the nearby beel. A couple of kilos was an easy catch for a day. People used to be happier and more content. Now the water is totally polluted. Even the water god can’t live in the water anymore. In the Tirap river we didn’t even need to use any fishing rods. We would just throw rice and the fish would rush to grab it. Now all the waste from the hills runs into the water. I remember the blue waters of the river. Now you can’t even go for a swim in it.”

On being asked about the role of coal mining in the region and its open nature, the king said, “Coal mining is the major reason why the fish can’t survive in the rivers anymore. The system has developed in such a way that it has erased moral judgment from the minds of the people. This has only spelt doom for the people. In fact it is very easy to track these operations if someone has the good will to do so. You drive along the main roads and any off road that goes into the forest will take you to the coal mines. Everybody is aware of this. But we do not have any authority over there, do we?”

Who is to be held accountable for such a situation? If this activity has continued over so many years, is it not easy for the tribal leaders like Bissa Raja to point out the perpetrators of this crime? To this, the Raja answered, “Whom will you blame? It is just like Corona. The way the disease spread from one to the other and then infected innumerable people, the same is with this syndicate. From an eight year old child to aged adults, all are involved in the trade one way or the other. We believe that Indra resides in those hills, it rains according to his will. Now even the God is helpless.”

Due to the depletion of the forest cover, the people in the region have also been exposed to frequent instances of man-animal conflict. Many cases have been reported where elephants venture into the tea gardens as well as villages and farms in search of food. Bissa Raja expressed his opinion regarding the same. He said, “We have a belief that wild animals venturing into villages is a bad omen. But now we get to see such cases very frequently. Let alone villages, tigers and deers have ventured even into townships and cities. In the absence of shelter and food where will the poor animals go?”

In fact, he also holds his tribe’s claim to fame, the tea trade, responsible for the exploitation of the forest. “Eti koli duti paat, koli jugor kheti.” he tells us in Assamese. It means, the cultivation of the two leaves one bud (literary phrase used to symbolize the tea cultivation) is a cultivation of the mythical Age of Downfall. “My forefathers gave this plant to the Britishers. But we never cultivated it as an industrial crop. It grew in the wild or was a part of home gardens. The colonial British were the first ones who destroyed large tracts of forest for the tea gardens. When tea began to be cultivated commercially, that marked the rise of oppression by the humans, both against nature as well as against fellow humans.”

The way forward

Bissa Raja ended his comments with another philosophical adage. “Our ancestors used to have a saying; do you need fish or do you need the lake? If you choose the fish, you eat for a couple of days but if you choose the lake, your future is secured. Nowadays nobody chooses the lake and everyone goes for the fish.”

The benefits of any venture can be evaluated by its sustainability along with the sustainability of the various factors that are dependent on it. The depletion of an age old forest for an energy resource that lasts half the life span of an average human being can never be considered sustainable. Like the Tai Phakes, the Singphos and their practices of animism also have traditional attachment to the hills and rivers that form the Dehing Patkai rainforest. Any decision regarding the future of the forest must thus be taken by considering its age old relations with people who have been calling it home since way before the first instances of its depletion.

Written by AxomSon

Readers like you make Inside Northeast’s work possible.

To support our brand of fearless and investigative journalism, support us HERE.

Download:

The Inside Northeast app HERE for News, Views, and Reviews from Northeast India.

Do keep following us for news on-the-go. We deliver the Northeast.

Copyright©2026 Living Media India Limited. For reprint rights: Syndications Today